6. Lung cancer

6.1 Summary

Lung cancer was the third most common cancer in Ireland, accounting for 10% of all malignant neoplasms, excluding non-melanoma skin cancer, in women and 15% in men (Table 6.1). The average number of new lung cancer cases diagnosed each year was 1,000 in women and 1,602 in men. During 1995-2007, the number of new cases diagnosed increased by approximately 3% per annum for women and 1% for men.

The risk of developing lung cancer up to the age of 74 was 1 in 37 for women and 1 in 20 for men, and was higher in NI than in RoI for both males and women. At the end of 2008, 708 women and 768 men aged under 65, and 1,330 women and 1,577 men aged 65 and over, were alive up to 15 years after their lung cancer diagnosis.

Table 6.1 Summary information for lung cancer in Ireland, 1995-2007

Ireland | RoI | NI | ||||

females | males | females | males | females | males | |

% of all new cancer cases | 7% | 11% | 7% | 10% | 8% | 12% |

% of all new cancer cases excluding non-melanoma skin cancer | 10% | 15% | 9% | 14% | 10% | 16% |

average number of new cases per year | 1000 | 1602 | 649 | 1052 | 351 | 551 |

cumulative risk to age 74 | 2.7% | 5.1% | 2.6% | 4.9% | 2.9% | 5.5% |

15-year prevalence (1994-2008) | 2038 | 2345 | 1394 | 1565 | 644 | 780 |

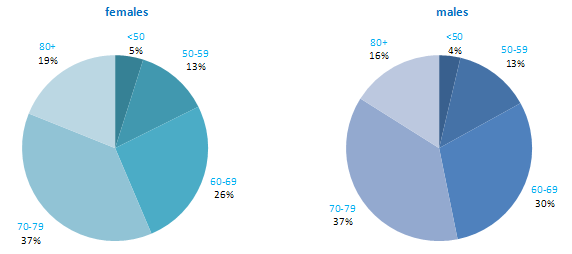

Lung cancer is mostly a disease of older people—the majority of cases occurred in those aged 70 and over (Figure 6.1). Less than 5% of cases presented in persons aged under 50.

Figure 6.1 Age distribution of lung cancer cases in Ireland, 1995-2007, by sex

6.2 International variations in incidence

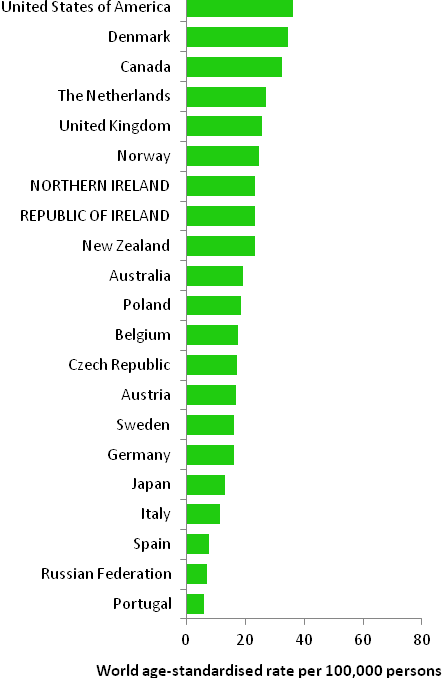

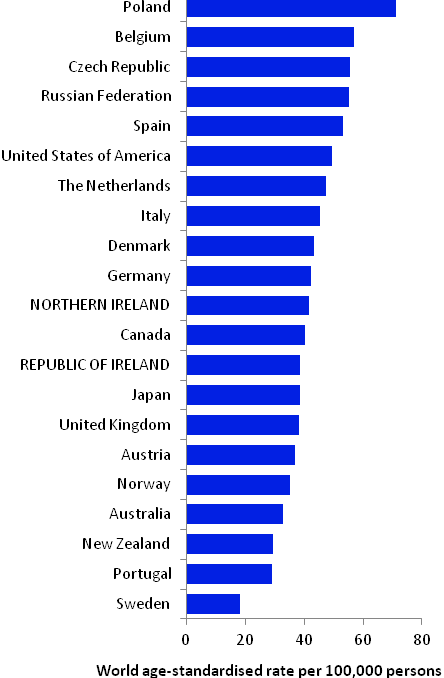

Incidence rates for lung cancer varied considerably among developed countries, particularly among men (Figure 6.2). Poland demonstrated the highest male rates, while USA, Denmark and Canada had the highest female rates. Rates were lowest among men in Sweden, and in Portugal and Russia among women. Lung cancer risk in both RoI and NI was close to the median compared to other developed countries for men, but was slightly above the median for women.

Figure 6.2 Estimated incidence rate per 100,000 in 2008 for selected developed countries compared to 2005-2007 incidence rate for RoI and NI: lung cancer | |

| females | males |

|  |

Source: GLOBOCAN 2008 (Ferlay et al., 2008) (excluding RoI and NI data, which is derived from cancer registry data for 2005-2007) | |

6.3 Risk factors

Table 6.2 Risk factors for lung cancer, by direction of association and strength of evidence

Increases risk | Decreases risk | |

Convincing or probable | Tobacco smoking and involuntary (passive) smoking1 | Fruit18 |

| Radon2 | |

| Ionizing radiation2 | |

| Arsenic and arsenic compounds; asbestos; beryllium and beryllium compounds; cadmium and cadmium compounds; chromium compounds; nickel compounds; silica dust; and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)3-7 | |

| Employment as a painter8 | |

| Beta-carotene supplements9,10 | |

| History of tuberculosis11 | |

| Indoor emissions from household combustion of coal1,12 | |

| Low socio-economic status13 | |

| Family history of lung cancer14,15 | |

Possible | Alcohol16 | Physical activity18,25 |

Coffee17 | Non-starchy or cruciferous vegetables18,26 | |

Low body fatness/leanness18 | Flavonoids from foods27 | |

Infection with chlamydia pneumoniae or Helicobacter pylori19,20 | Green tea28 | |

Occupational exposure to diesel motor exhaust or organic dust21,22 | Employment in cotton textile and agriculture industries29 | |

Hormone replacement therapy23,24 | Aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs30 | |

| ||

1 Secretan et al., 2009; 2 El Ghissassi et al., 2009; 3 Celik et al., 2008; 4 Baan et al., 2009; 5 Lacasse et al., 2009; 6 Straif et al., 2009; 7 main route of exposure is occupational; 8 Guha et al., 2010; 9 in current smokers; 10 Tanvetyanon and Bepler, 2008; 11 Liang et al., 2009; 12 Hosgood et al., 2010; 13 Sidorchuk et al., 2009; 14 one or more relative(s) with lung cancer; 15 Lissowska et al., 2010; 16 Uehara and Kiyohara, 2010; 17 Tang et al., 2010; 18 World Cancer Research Fund / American Institute for Cancer Research, 2007; 19 Zhan et al., 2011; 20 Zhuo et al., 2009; 21 Olsson et al., 2011; 22 Peters et al., 2011; 23 in non-smoking women; 24 Greiser et al., 2010; 25 International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2002; 26 Lam et al., 2009; 27 Tang et al., 2009a; 28 Tang et al., 2009b; 29 Lenters et al., 2010; 30 Bosetti et al., 2006 | ||

Smoking is the principal cause of lung cancer (Table 6.2). In populations with prolonged cigarette use, 90% of lung cancer cases are due to cigarette smoking (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2004b). Risk increases with younger age at smoking commencement and longer duration of smoking. Stopping smoking, at any age but particularly so before middle age, avoids most of the subsequent risk (Peto et al., 2000). In addition, involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke (passive smoking) is a cause of lung cancer in those who have never smoked. The consistent relationship between higher lung cancer risk and lower socio-economic status probably reflects social class variations in tobacco exposure.

The chances of developing lung cancer are increased in those exposed to radon, ionizing radiation and a variety of chemicals and compounds. Various lifestyle factors (such as alcohol intake, physical activity, leanness and aspects of diet) may be related to lung cancer, but it is not always possible to rule out the possibility that the associations are due to a residual effect of smoking.

6.4 Small geographic area characteristics and cancer risk

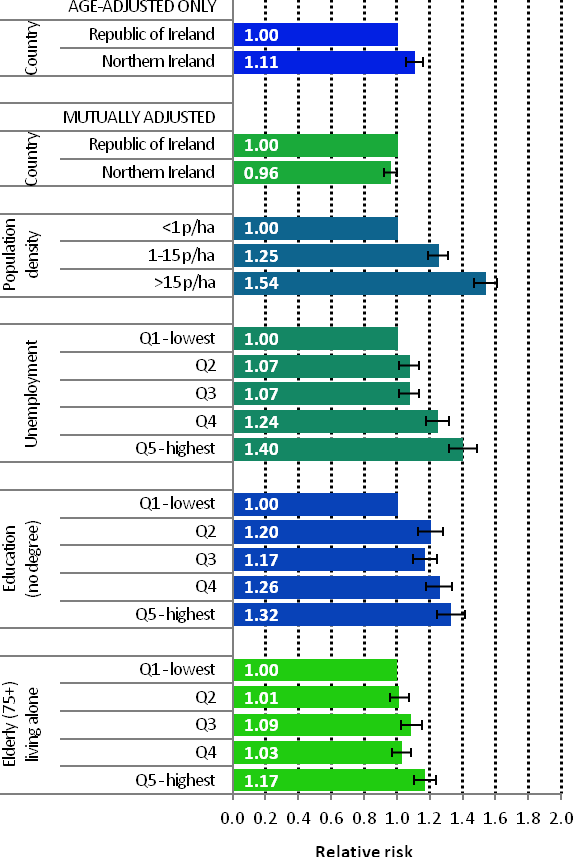

Figure 6.3 Adjusted relative risks (with 95% confidence intervals) of lung cancer by socio-economic characteristics of geographic area of residence: males

| MalesAmong men lung cancer risk was higher in NI than RoI (RR=1.11, 95%CI=1.06-1.16) (Figure 6.3). This difference disappeared when adjusted for population density and socio-economic characteristics. There was a strong association between population density and lung cancer for men, with the risk 54% greater in high density than in low density areas. Electoral wards and districts with the highest levels of unemployment had higher rates of male lung cancer than those with the lowest levels. The relative risk between the highest and lowest quintiles was 1.40 (95%CI=1.32-1.49). A strong association also existed between lower educational attainment and male lung cancer. Men in areas with the poorest education levels had a 32% greater risk of lung cancer than men living in the areas with the highest level of educational attainment. Areas with the highest proportions of elderly living alone also had an elevated risk of lung cancer among men. |

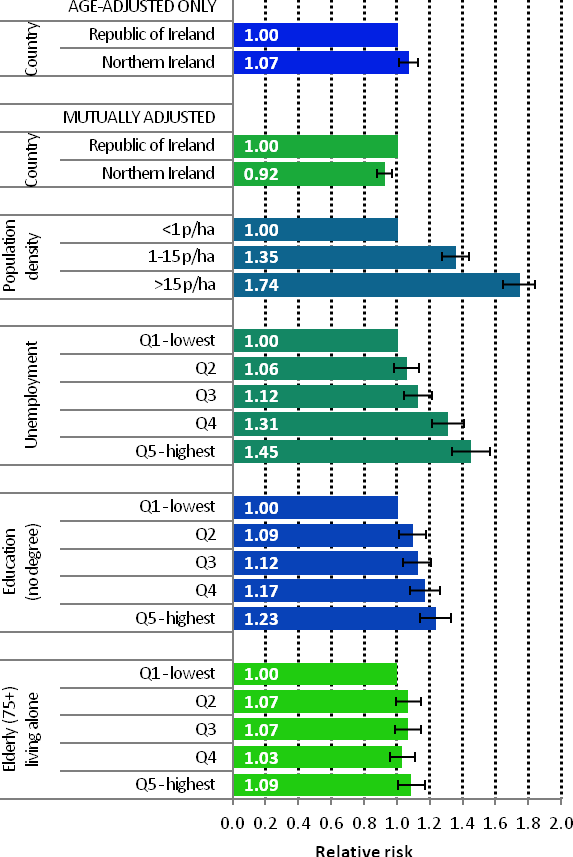

Figure 6.4 Adjusted relative risks (with 95% confidence intervals) of lung cancer by socio-economic characteristics of geographic area of residence: females

| FemalesAmong women, lung cancer risk was higher in NI compared to RoI (RR=1.07, 95%CI=1.01-1.13) (Figure 6.4). However, adjusting for population density and socio-economic factors reversed this relationship, with risk lower in NI (RR=0.92, 95%CI=0.88-0.97). For women the association between lung cancer and population density was greater than for men, with lung cancer risk 74% higher in high density compared to low density areas. Lung cancer among women was higher in areas of high unemployment, lower levels of degree level education and with a high proportion of elderly living alone. The relative risk for people living in areas with the highest proportion of these indicators was 45%, 23% and 9% respectively, compared to the areas with the lowest proportion of these indicators. |

6.5 Mapping and geographical variation

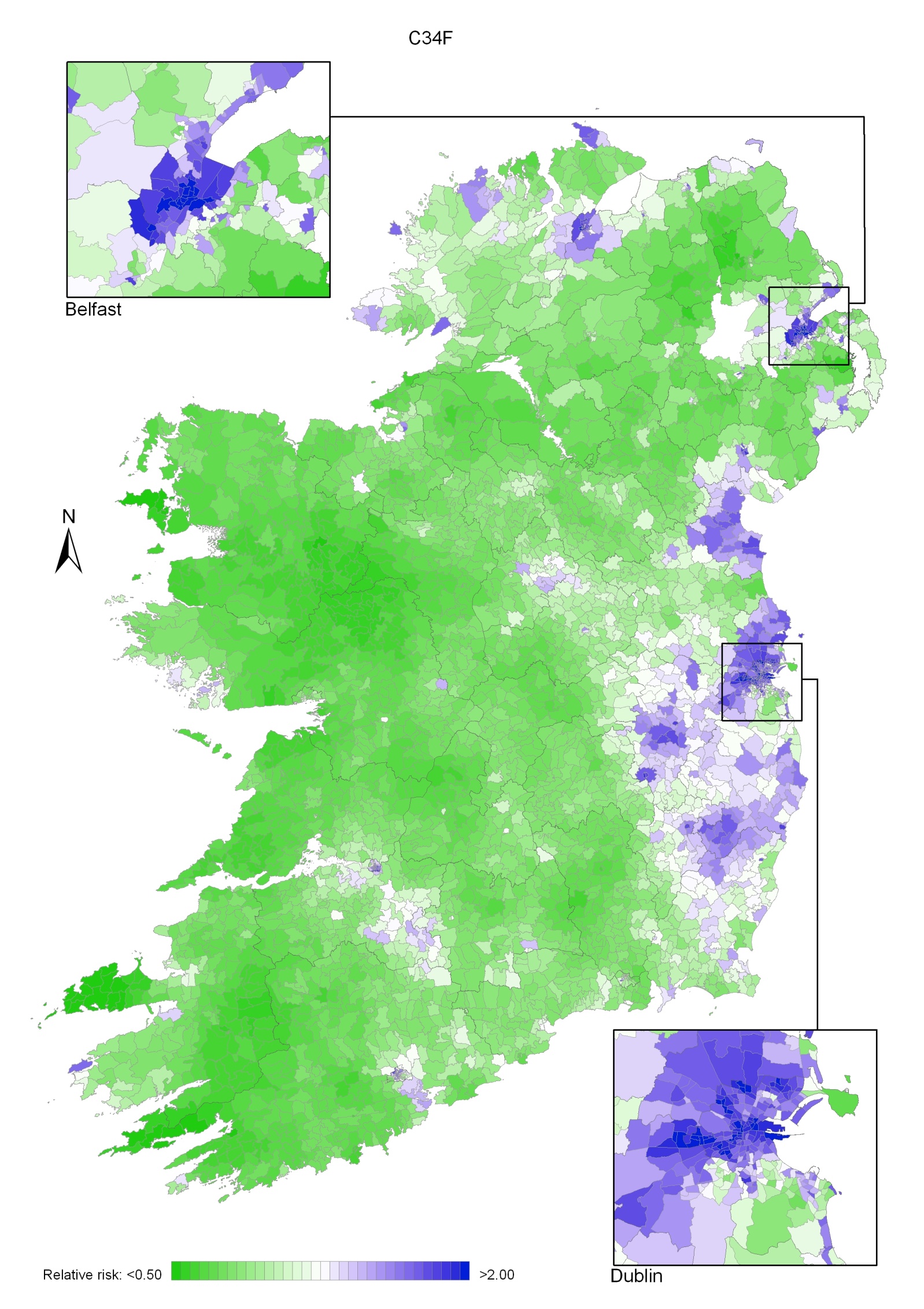

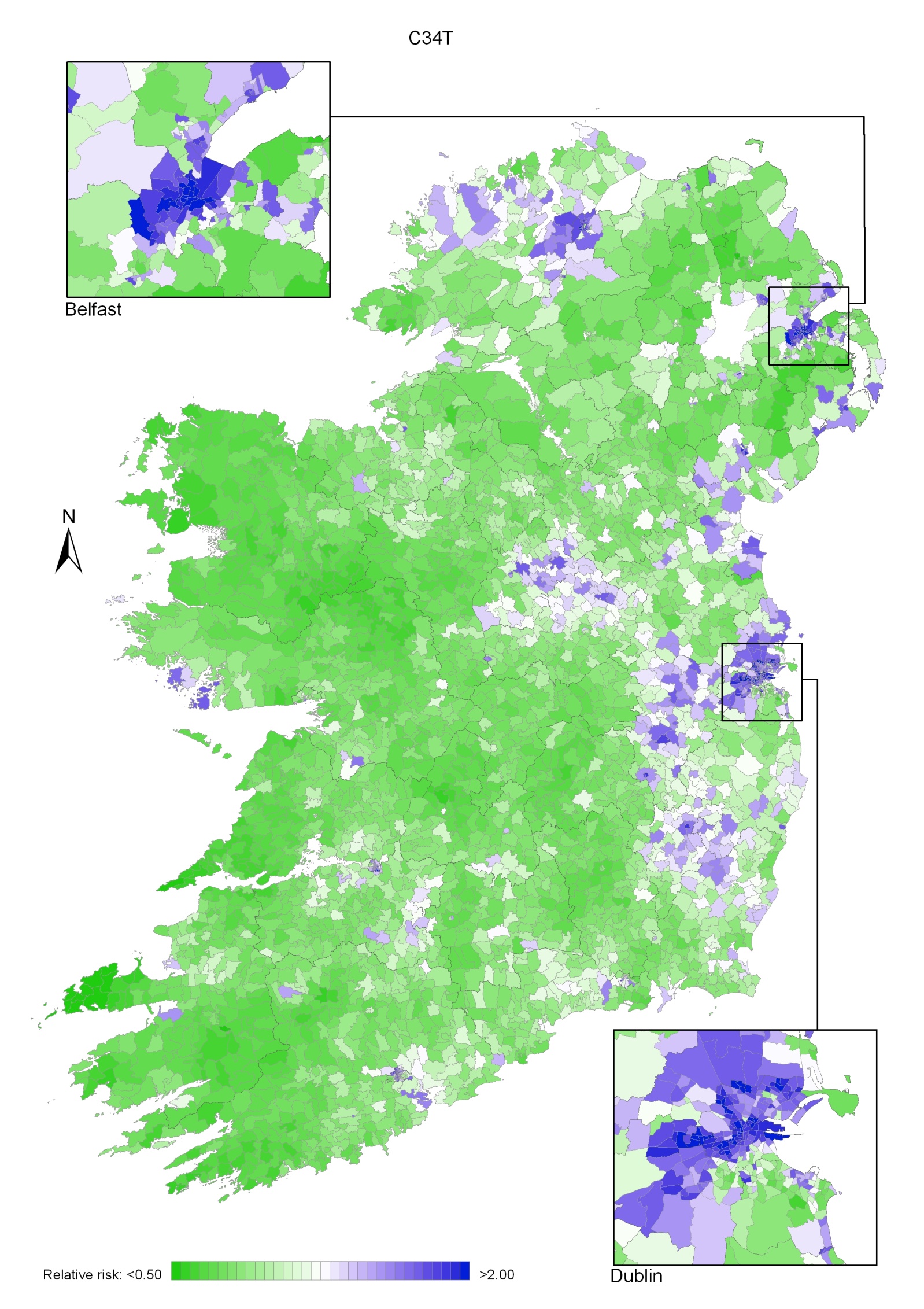

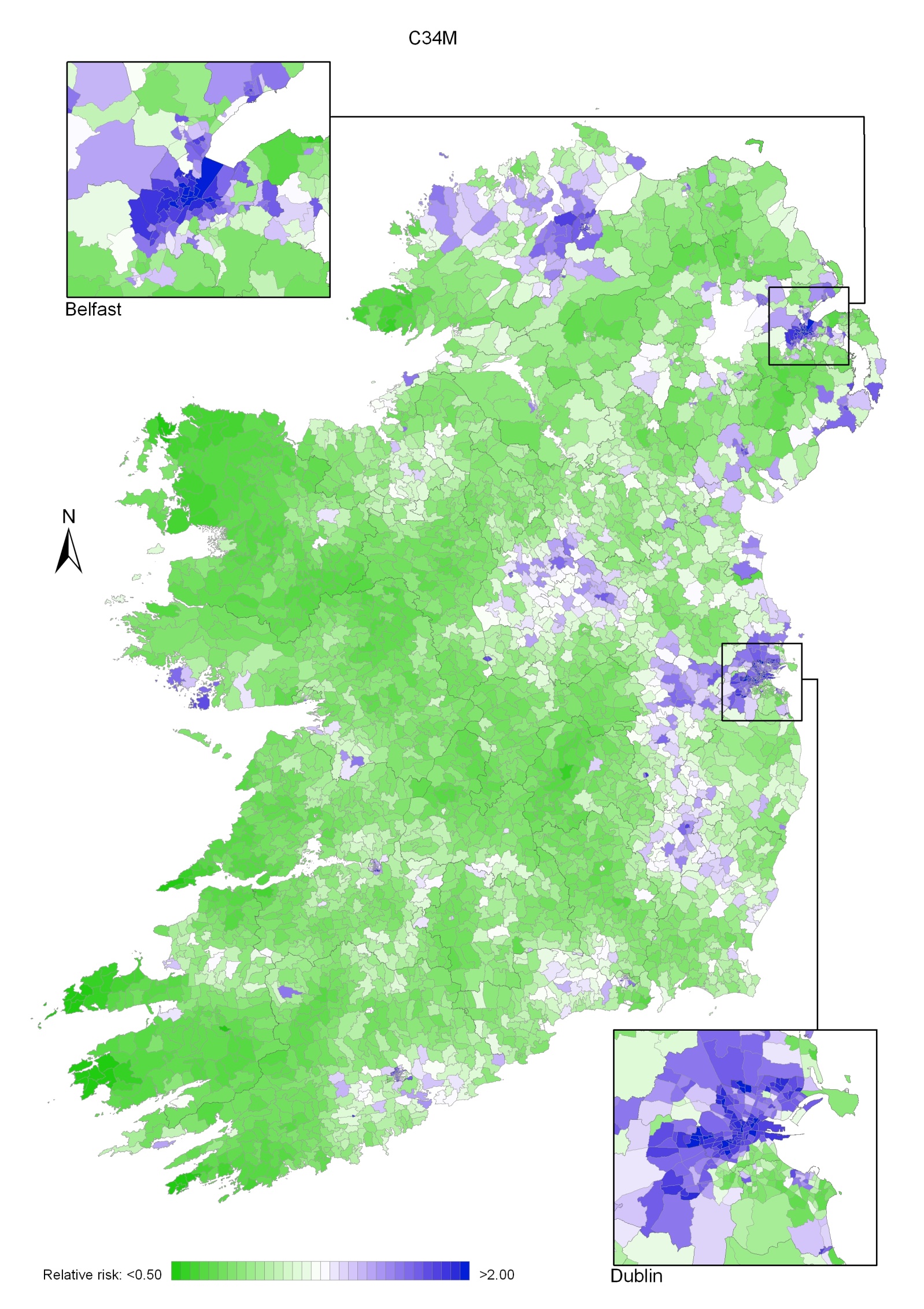

The geographical pattern of the relative risk of lung cancer was similar for men and women (Maps 6.1-6.3).

For both sexes combined, areas of higher relative risk were seen in Leinster, including Dublin (north and west), Kildare, Carlow, Longford, Louth, Wicklow, Wexford and Westmeath. Belfast city, Derry and Donegal also showed higher relative risk; other scattered areas of higher risk included Cork, Galway, Waterford, Newry and Mourne, Down, Ards, Carrickfergus, Larne and Moyle. In Dublin, the risk was higher in the north and south-west of the city and, in Belfast, in the central city area (Map 6.1).

In Dublin city, the risk was higher on the north side and, in Belfast, in the north and west areas. The pattern for men was similar to that for both sexes combined, due to the higher incidence in men compared to women (Map 6.2).

The pattern for women showed higher relative risk in Leinster, concentrated in Dublin, Kildare, Carlow, Wicklow, Wexford and Louth, and in the Belfast and Derry areas. There were some smaller areas of higher risk in Donegal, Carrickfergus, Newry and Mourne and Down (Map 6.3).

Map 6.1 Lung cancer, smoothed relative risks: both sexes

Map 6.2 Lung cancer, smoothed relative risks: males

Map 6.3 Lung cancer smoothed relative risks: females