Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) consists of a group of more than 20 different malignant lymphoproliferative diseases that originate from lymphocytes. NHL was the fifth most common cancer in Ireland, accounting for 3.4% of all malignant neoplasms, excluding non-melanoma skin cancer, in women and 3.6% in men (Table 8.1). The average number of new cases diagnosed each year was approximately 354 in women and 392 in men. During 1995-2007, the number of new cases diagnosed increased by approximately 3% per annum overall.

The risk of developing NHL up to the age of 74 was 1 in 102 for women and 1 in 80 for men, and was higher in NI than in RoI for both males and females. At the end of 2008, 1,255 females and 1,607 males aged under 65, and 1,477 females and 1,266 males aged 65 and over, were alive up to 15 years after their NHL diagnosis.

Table 8.1 Summary information for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in Ireland, 1995-2007

Ireland | RoI | NI | ||||

females | males | females | males | females | males | |

% of all new cancer cases | 2.5% | 2.6% | 2.3% | 2.5% | 2.9% | 2.8% |

% of all new cancer cases excluding non-melanoma skin cancer | 3.4% | 3.6% | 3.2% | 3.5% | 3.8% | 3.8% |

average number of new cases per year | 354 | 392 | 224 | 265 | 130 | 127 |

cumulative risk to age 74 | 1.0% | 1.2% | 0.9% | 1.2% | 1.1% | 1.3% |

15-year prevalence (1994-2008) | 2732 | 2873 | 1782 | 1944 | 950 | 929 |

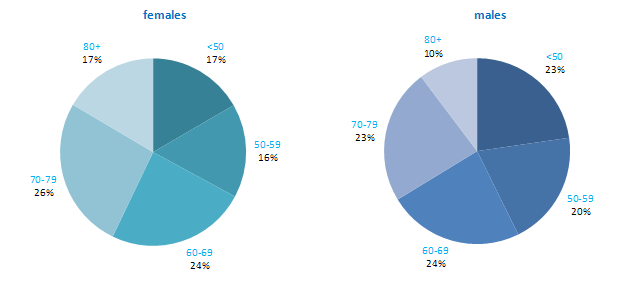

Age at diagnosis of NHL was younger for men than for women—43% of cases presented in men under 60 compared to 33% of women (Figure 8.1). Approximately 17% of women and 10% of men were aged 80 years or older at diagnosis. Age at diagnosis was also slightly younger in RoI than in NI.

Figure 8.1 Age distribution of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma cases in Ireland, 1995-2007, by sex

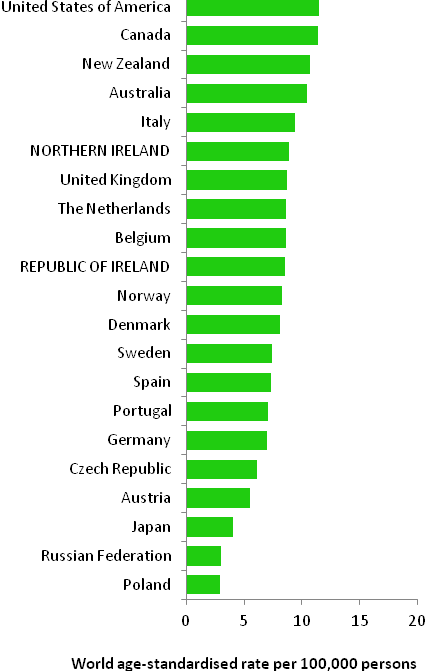

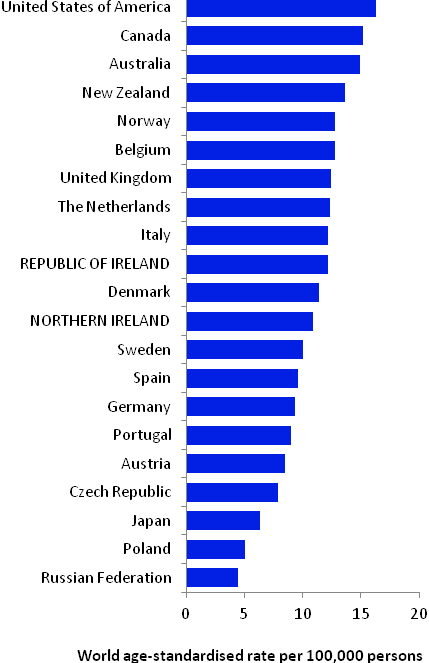

Among developed countries the USA had the highest incidence rate of NHL for men and women, while Canada had the second highest rates for both sexes. Both RoI and NI had close to median rates of the disease for men and women, while Poland, Russia and Japan had the lowest rates.

Figure 8.2 Estimated incidence rate per 100,000 in 2008 for selected developed countries compared to 2005-2007 incidence rate for RoI and NI: non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | |

| females | males |

|  |

Source: GLOBOCAN 2008 (Ferlay et al., 2008) (excluding RoI and NI data, which is derived from Cancer Registry data for 2005-2007) NOTE: NHL was defined in GLOBOCAN by ICD10 codes C82-C85 & C96. In the atlas we have included codes C82-C85 only in the definition of NHL (see Table 2.1.) The data for NI and RoI in Figure 8.2 retain this definition, while those for other countries include C96. Due to changes in case definition, inclusion of C96 in the RoI data would have artificially inflated the incidence figures. | |

Table 8.2 Risk factors for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, by direction of association and strength of evidence

Increases risk | Decreases risk | |

Convincing or probable | Immune deficiency1,2,3 | |

| Some auto-immune disorders4 | |

| Various infections, including human immunodeficiency virus, type1 (HIV-1), Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV), human T-cell lymphotrophic virus type 1 (HTLV-1), hepatitis C (HCV), and Helicobacter pylori5 | |

| Occupational exposure to benzene, ethylene oxide, and formaldehyde6,7 | |

| Employment in the rubber manufacturing industry6 | |

| Family history of NHL, Hodgkin’s lymphoma or leukaemia8,9 | |

Possible | Occupational exposure to pesticides and trichloroethylene10,11 | Sun exposure16 |

Tobacco smoking12 | Allergic conditions and/or atopy17,18 | |

Overweight/obesity13,14,15 | ||

1 individuals with a weakened immune system; users of immunosuppressive drugs; 2 Grulich and Vajdic, 2005; 3 Grosse et al., 2009; 4 Ekstrom Smedby et al., 2008; 5 Bouvard et al., 2009; 6 Baan et al., 2009; 7 National Toxicology Program, 2008; 8 one or more first degree relative(s) affected; 9 Wang et al., 2007; 10 Mandel et al., 2006; 11 US Department of Health and Human Services, 2011; 12 Morton et al., 2005; 13 Larsson and Wolk, 2007; 14 Renehan et al., 2008; 15 Willett et al., 2008; 16 Kricker et al., 2008; 17 hay fever, asthma, food allergy, but not eczema; 18 Vajdic et al., 2009 | ||

Although lymphomas may occur in children, the following description of risk factors relates to NHL in adults.

The best described risk factor for NHL is immune deficiency (Table 8.2). Individuals who have had organ transplants, or who take immunosuppressive drugs to prevent organ rejection or to treat various autoimmune conditions (e.g. azathioprine and ciclosporin) have a high risk of NHL. Risk is also increased in individuals with some auto-immune disorders, including Sjorgen syndrome, systemic lupus and haemolytic anaemia. A variety of infection—including human immunodeficiency virus, type 1 (HIV-1) which causes AIDS, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which is a common member of the herpesvirus family, and hepatitis C virus (HCV)—can cause NHL, often acting via effects on immunosuppression or inflammation.

Occupational exposure to ethylene oxide (an organic compound used in the manufacture of products like polyethylene), benzene (an industrial solvent and precursor to basic industrial chemicals including drugs, plastics, synthetic rubber, and dyes) and formaldehyde (used in the production of industrial resins that are then used in the manufacture of products such as adhesives and binders for wood products, plastic and synthetic fibres) are all associated with NHL. Those exposed to pesticides through their work, or to tricholoroethylene, a hydrocarbon commonly used as an industrial solvent, may also have increased risk of NHL, but the evidence is less certain. Workers in the rubber manufacturing industry are also at increased risk, but due to the complexity of exposures in this industry, the causative agents have not yet been identified.

Risk of NHL is increased by around 50% in those who report first-degree relatives with NHL, Hodgkin’s lymphoma or leukaemia. In terms of lifestyle factors, current smoking may increase the risk of follicular lymphomas, but not other subtypes. A modest positive association between weight and NHL risk is evident in meta-analyses, but this may be limited to particular subtypes and/or to obese individuals. Increased recreational sun exposure may be associated with a modestly reduced risk of particular types of NHL, while individuals with allergic conditions, such as hay fever or asthma, or atopy may have slightly reduced risk of B-cell NHL.

Figure 8.3 Adjusted relative risks (with 95% confidence intervals) of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma by socio-economic characteristics of geographic area of residence: males

| MalesAmong men there was little variation in risk of NHL across Ireland, by population density or socio-economic factors. In particular, differences between NI and RoI were not statistically significant (Figure 8.3). |

Figure 8.4 Adjusted relative risks (with 95% confidence intervals) of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma by socio-economic characteristics of geographic area of residence: females

| FemalesAs for men, there was little variation in risk of female NHL across Ireland by population density or socio-economic factors (Figure 8.4). However risk of NHL among women was 14% greater in NI than in RoI. This difference was not reduced by adjustment for population density or socio-economic factors. |

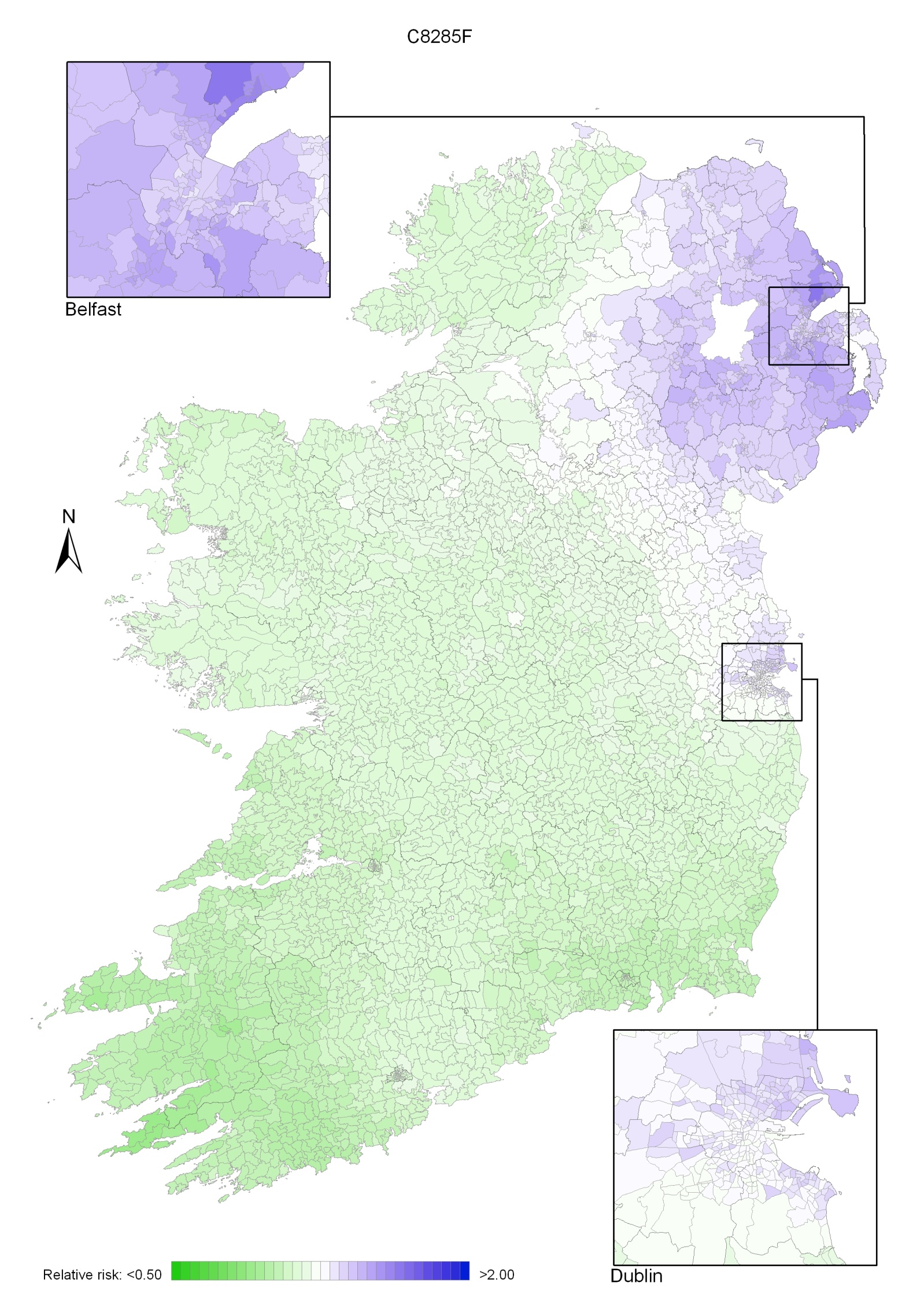

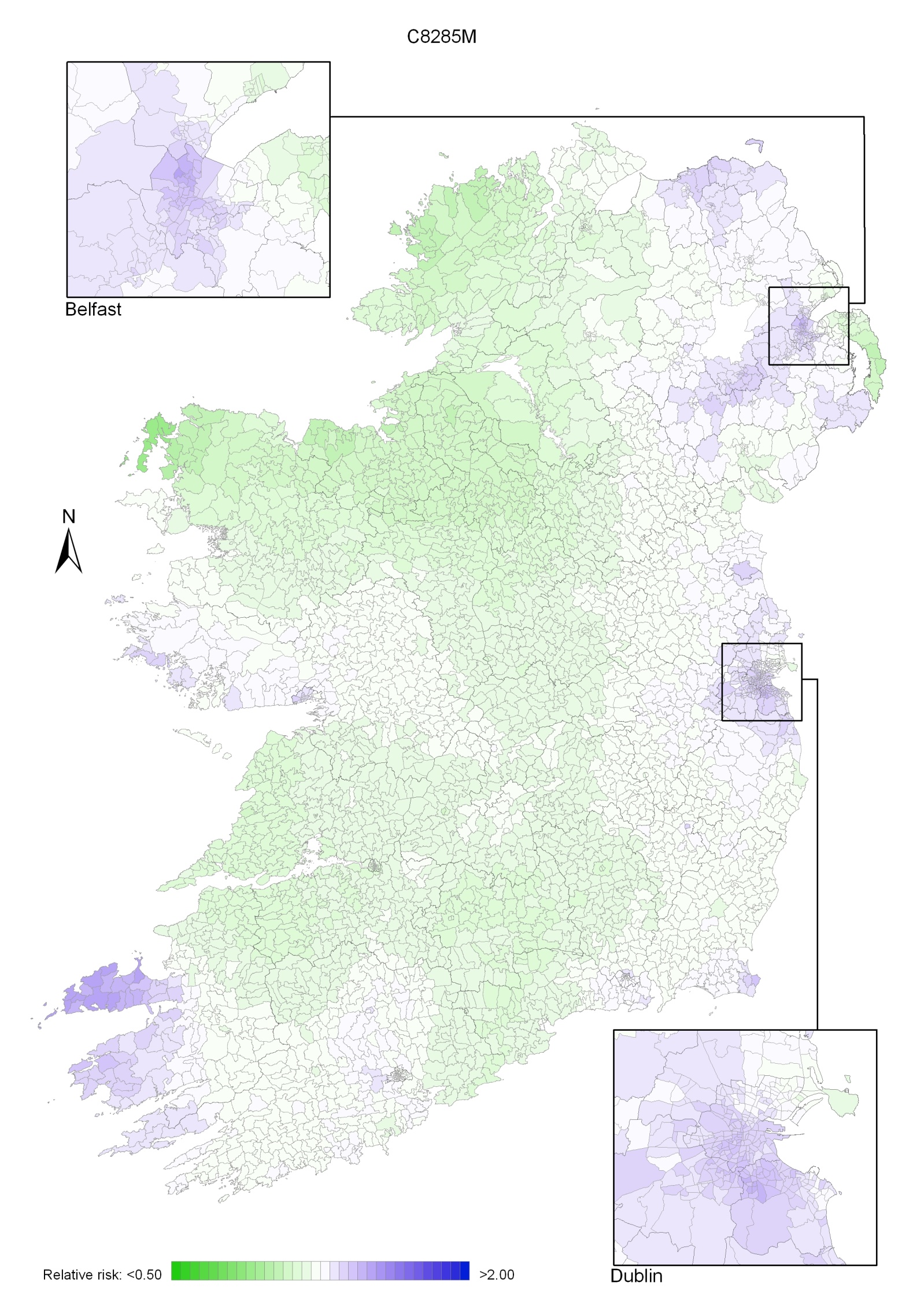

The geographical variation in relative risk of NHL was fairly modest. For both sexes combined, there was an area of higher relative risk in the north-east, extending to Dublin, but the remainder of the country showed only modest variation (Map 8.1).

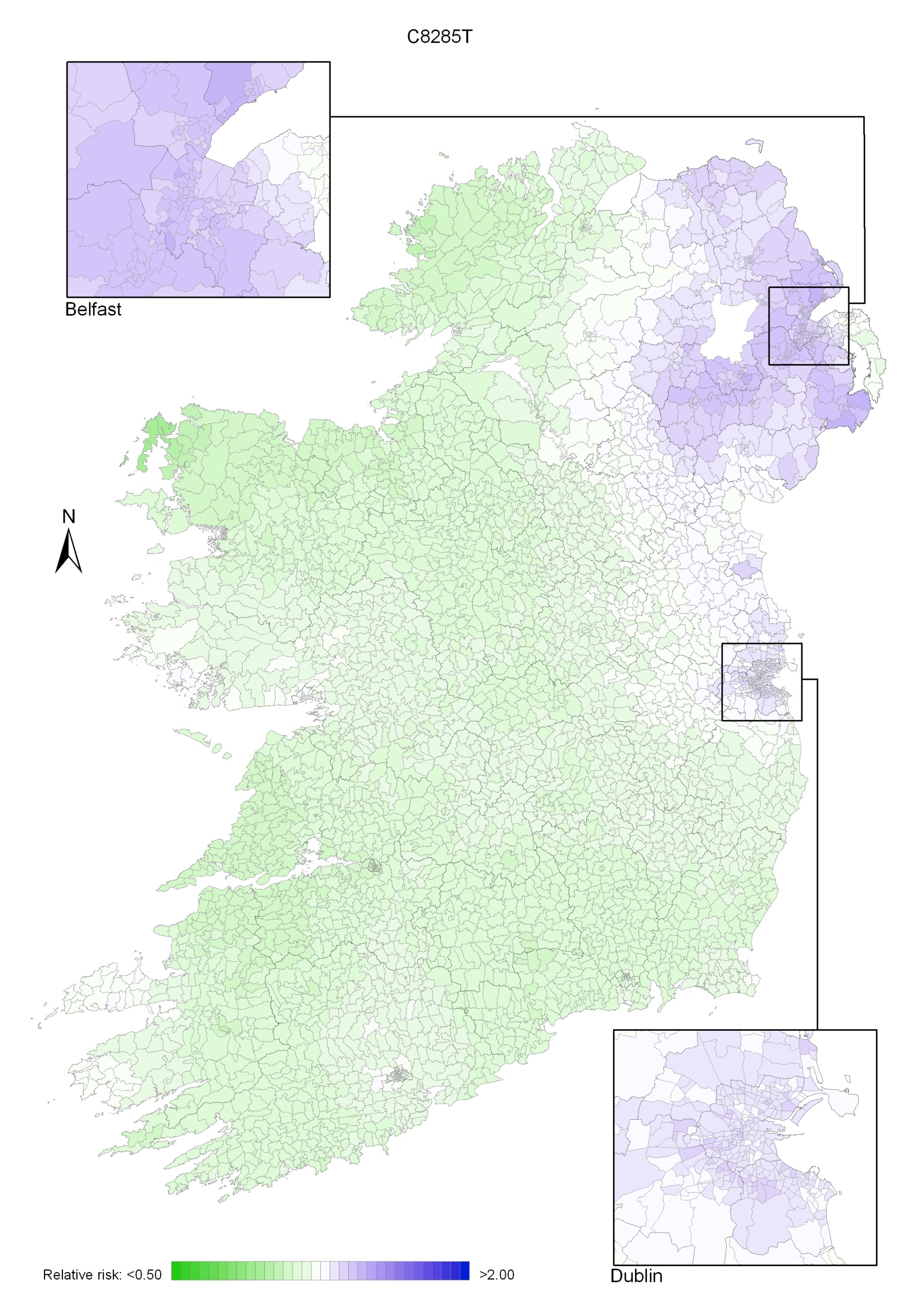

The same area of higher risk occurred for men but was less prominent (Map 8.2). The map for men also showed areas of higher relative risk in Kerry and Galway.

Women showed higher relative risk in the north-east of the island extending southwards to Dublin; this was more pronounced than for men (Map 8.3).

Map 8.1 Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, smoothed relative risks: both sexes

Map 8.2 Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, smoothed relative risks: males

Map 8.3 Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, smoothed relative risks: females