Bladder cancer was the fourth most common cancer in Ireland for men and the twelfth most common for women, accounting for 1.9% of all malignant neoplasms, excluding non-melanoma skin cancer, in women and 4.4% in men (Table 11.1). The average number of new cases diagnosed each year was 193 in women and 479 in men. During 1995-2007, the number of new cases diagnosed per annum remained fairly constant.

The risk of developing bladder cancer up to the age of 74 was 1 in 212 for women and 1 in 72 for men and was slightly higher in RoI than in NI. At the end of 2008, 326 women and 787 men aged under 65, and 981 women and 2,527 men aged 65 and over, were alive up to 15 years after their bladder cancer diagnosis.

Table 11.1 Summary information for bladder cancer in Ireland, 1995-2007

Ireland | RoI | NI | ||||

females | males | females | males | females | males | |

% of all new cancer cases | 1.4% | 3.1% | 1.4% | 3.1% | 1.3% | 3.2% |

% of all new cancer cases excluding non-melanoma skin cancer | 1.9% | 4.4% | 1.9% | 4.4% | 1.8% | 4.4% |

average number of new cases per year | 193 | 479 | 133 | 331 | 60 | 147 |

cumulative risk to age 74 | 0.5% | 1.4% | 0.5% | 1.4% | 0.4% | 1.3% |

15-year prevalence (1994-2008) | 1307 | 3314 | 972 | 2346 | 335 | 968 |

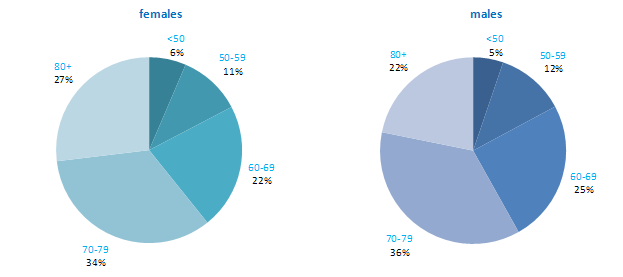

The distribution of age at diagnosis for bladder cancer was similar for men and women. Almost 60% of new cases were aged 70 or older at diagnosis (Figure 11.1). Only about 6% of cases presented at under 50 years of age. Age at diagnosis was slightly younger in RoI than in NI.

Figure 11.1 Age distribution of bladder cancer cases in Ireland, 1995-2007, by sex

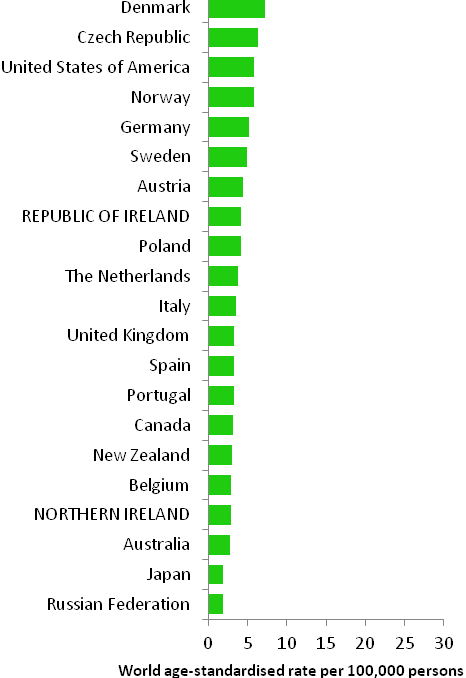

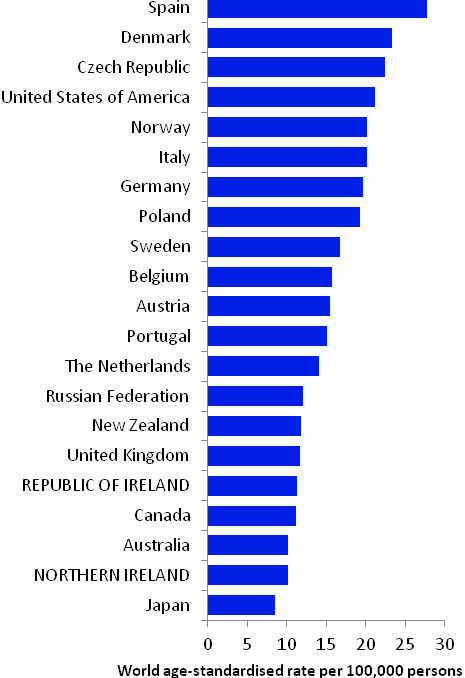

Male and female rates of bladder cancer in NI were among the lowest of the 21 developed countries examined, with RoI also having a comparatively low incidence in men but not women (Figure 11.2). Female rates were much lower overall than male rates, and varied somewhat less. Spain had the highest rate of bladder cancer among men, while Denmark had the highest rate among women. However, caution needs to be exercised in making international comparisons of bladder cancer incidence, as classification of the disease with regard to malignant and non-malignant cancers is not consistent across countries.

Figure 11.2 Estimated incidence rate per 100,000 in 2008 for selected developed countries compared to 2005-2007 incidence rate for RoI and NI: bladder cancer | |

| females | males |

|  |

Source: GLOBOCAN 2008 (Ferlay et al., 2008) (excluding RoI and NI data, which is derived from Cancer Registry data for 2005-2007) | |

Table 11.2 Risk factors for bladder cancer, by direction of association and strength of evidence

| Increases risk | Decreases risk |

Convincing or probable | Tobacco smoking1 | |

| Various occupations and employment in particular industries and product manufacture2-8 | |

| Occupational exposure to aromatic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons 3,4 | |

| Ionizing radiation9 | |

| Arsenic and inorganic arsenic compounds10 | |

Possible | Volume of tap water consumed11 | Having had children16 |

Disinfection by-products in drinking water12,13 | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (other than aspirin)17 | |

Type II diabetes14 | Selenium18 | |

Infection with human papilloma viruses (HPV)15 | ||

Early menopause16 | ||

| ||

1 Secretan et al., 2009; 2 Reulen et al., 2008; 3 Scélo and Brennan, 2007; 4 Baan et al., 2009; 5 Reulen et al., 2008; 6 Manju et al., 2009; 7 Guha et al., 2010; 8 Harling et al., 2010; 9 El Ghissassi et al., 2009; 10 Straif et al., 2009 11 Villaneuva et al., 2006; 12 Villanueva et al., 2004; 13 Costet et al., 2011; 14 Larsson et al., 2006; 15 Li et al., 2011; 16 Dietrich et al., 2011; 17 Daugherty et al., 2011; 18 Amaral et al., 2010 | ||

The leading known cause of cancer of the bladder is tobacco smoking (Table 11.2). Two-thirds of bladder cancers in men and one-third in women are considered to be due to smoking (Brennan et al., 2000; Brennan et al., 2001). Risk increases with duration of cigarette smoking and number of cigarettes smoked (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2004b). Risk is also increased in those who smoke pipes or cigars, but do not smoke cigarettes (Pitard et al., 2001). Stopping smoking results in an immediate decrease in risk (Scélo and Brennan, 2007).

A range of occupations (including painting, mining, bus driving, motor mechanic, blacksmith, machine setter and hairdressing) and employment in various industries or in manufacturing of specific products (including rubber manufacturing, aluminium production and magenta manufacture) are associated with bladder cancer. In terms of specific occupational exposures which cause bladder cancer, the most consistent evidence relates to aromatic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.

Other than smoking and occupational exposures, the factors involved in bladder cancer aetiology are largely unknown, although several putative relationships have been suggested. Positive associations have been reported between volume of tap water consumed and bladder cancer risk. This may be due to increased intake of carcinogenic chemicals contained in the water, such as arsenic (which is a recognised cause of bladder cancer) or disinfection by-products (e.g. trihalomethanes, the main by-product of chlorinated water), but the results of studies are not consistent.

Individuals with type II diabetes may have a modest increased risk of developing bladder cancer. A meta-analysis of studies investigating human papilloma virus (HPV) infection and bladder cancer estimated that risk could be increased by almost 3-fold in infected individuals. In another meta-analysis, bladder cancer risk was reduced by one-third in ever parous women (those who had had one or more children), and was elevated among those undergoing an early menopause. Non-smokers who regularly use non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs other than aspirin may have reduced bladder cancer risk, although aspirin use itself does not appear to be associated with risk. Those with higher levels of selenium measured in serum or toenails may also have lower risk.

Figure 11.3 Adjusted relative risks (with 95% confidence intervals) of bladder cancer by socio-economic characteristics of geographic area of residence: males | MalesAmong men the risk of bladder cancer was lower in NI than RoI (RR=0.92, 95%CI=0.87-0.97) (Figure 11.3). This difference increased when adjusted for population density and socio- economic characteristics (RR=0.83, 95%CI= 0.78-0.88). There was a strong association between population density and bladder cancer for men, with the risk 30% higher in high density areas than in low density areas. Wards and EDs with the highest levels of unemployment had a 10% higher risk of male bladder cancer than those with the lowest levels. There was no association between male bladder cancer and area-based education level. There was a trend of increasing risk with higher proportions of elderly living alone. Areas with the highest levels of elderly living alone had a 19% elevated risk of bladder cancer among men, compared to areas with the lowest levels. |

Figure 11.4 Adjusted relative risks (with 95% confidence intervals) of bladdercancer by socio-economic characteristics of geographic area of residence: females

| FemalesBladder cancer risk was also lower in women in NI compared to RoI (RR=0.86, 95%CI=0.79-0.93) (Figure 11.4). Adjusting for population density and socio-economic factors increased this difference (RR=0.79, 95%CI=0.72-0.87). The association between bladder cancer and population density was similar to that for men, with a 31% higher risk in high density, compared to low density, areas. As for men, there was no association between female bladder cancer and area-based education level. There was also no association with unemployment. Areas with the greatest proportion of elderly living alone had an 18% higher risk than those with the lowest proportion. |

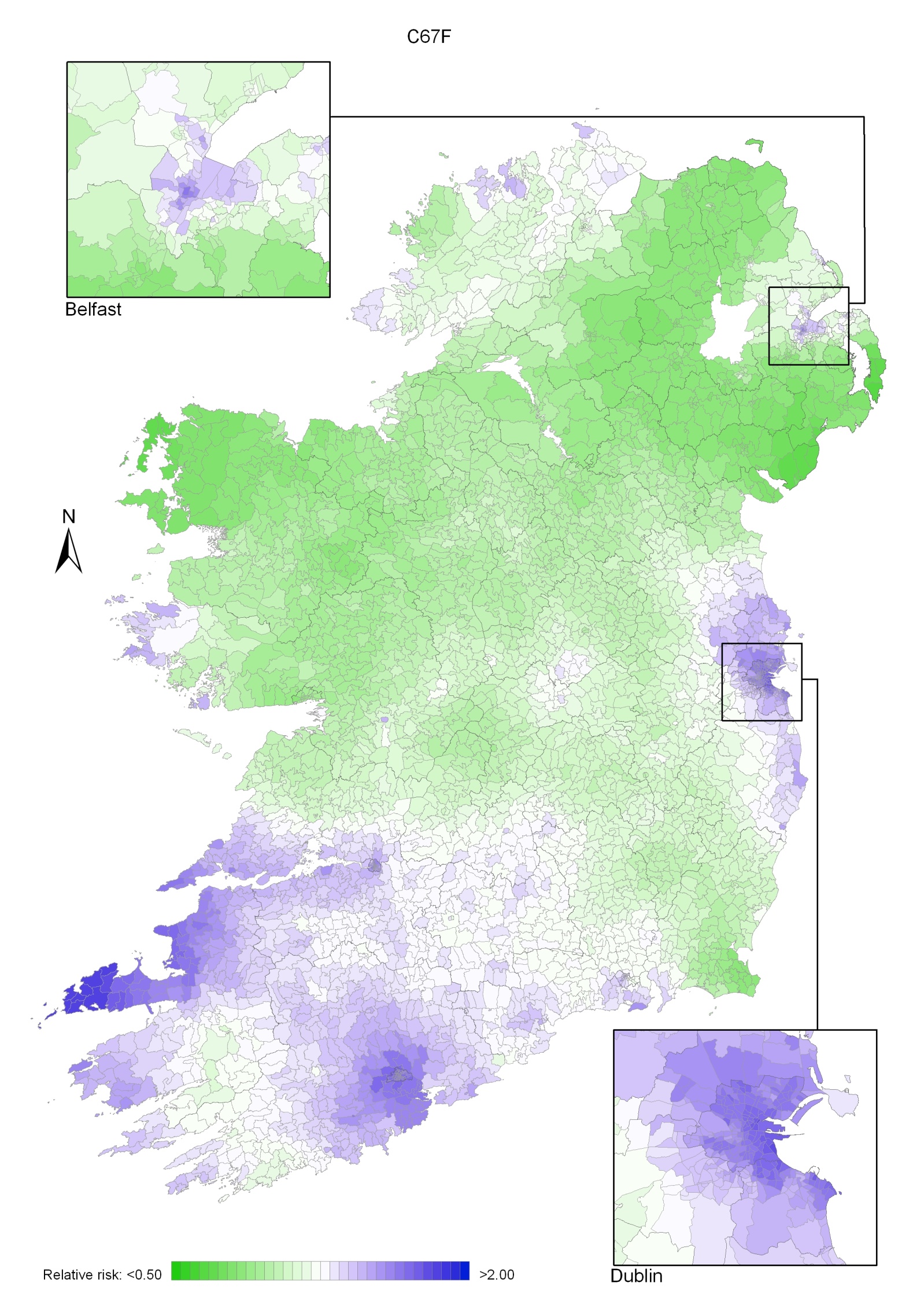

The geographical pattern of bladder cancer for both sexes was mainly determined by the pattern for men, due to their higher incidence rate (Map 11.1).

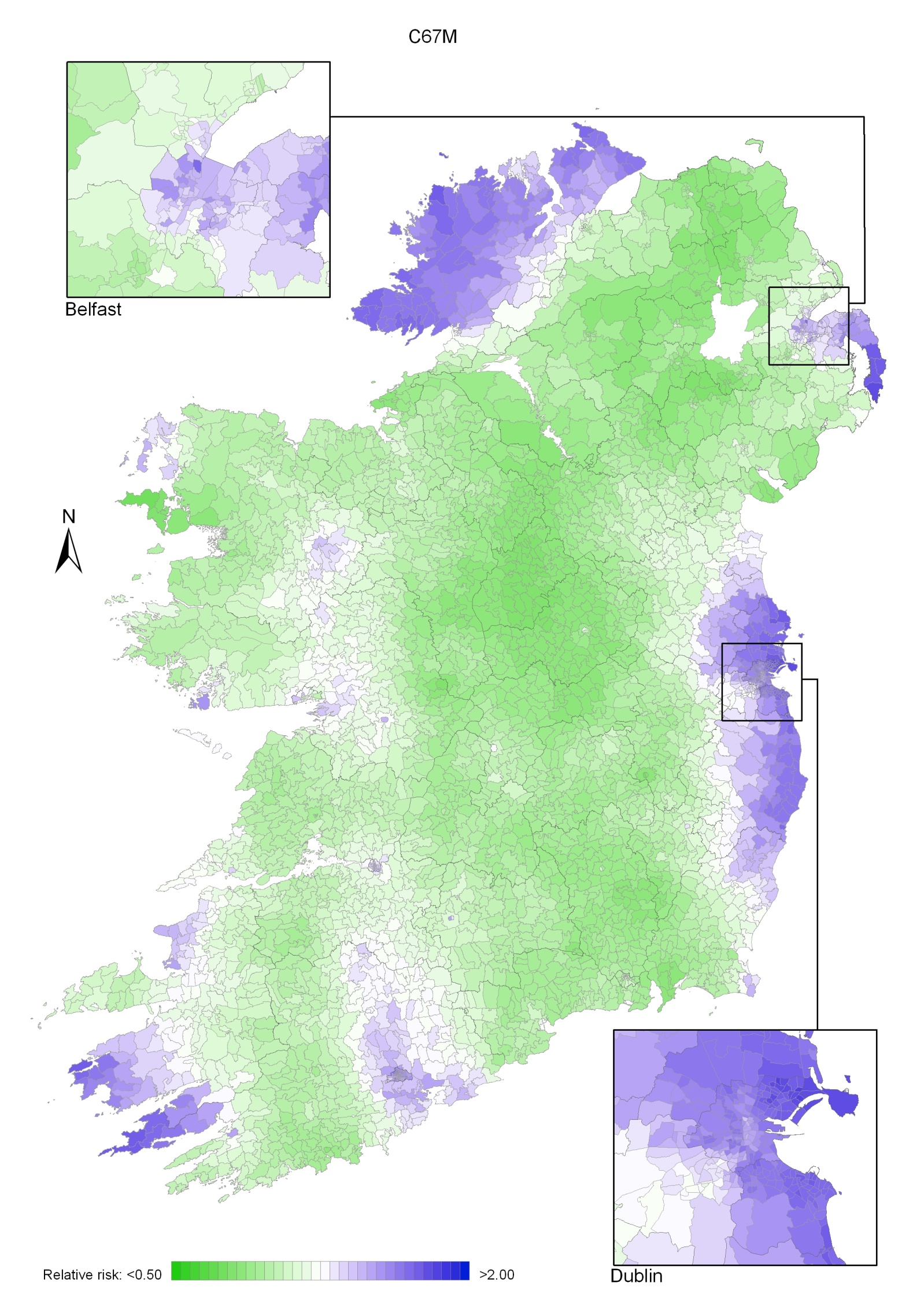

For men (Map 11.2), there were several areas of high relative risk, including the east coast from Louth to Wexford (including Dublin City), Donegal, and more scattered areas including parts of Kerry, Cork, North Down, Ards and north and east Belfast.

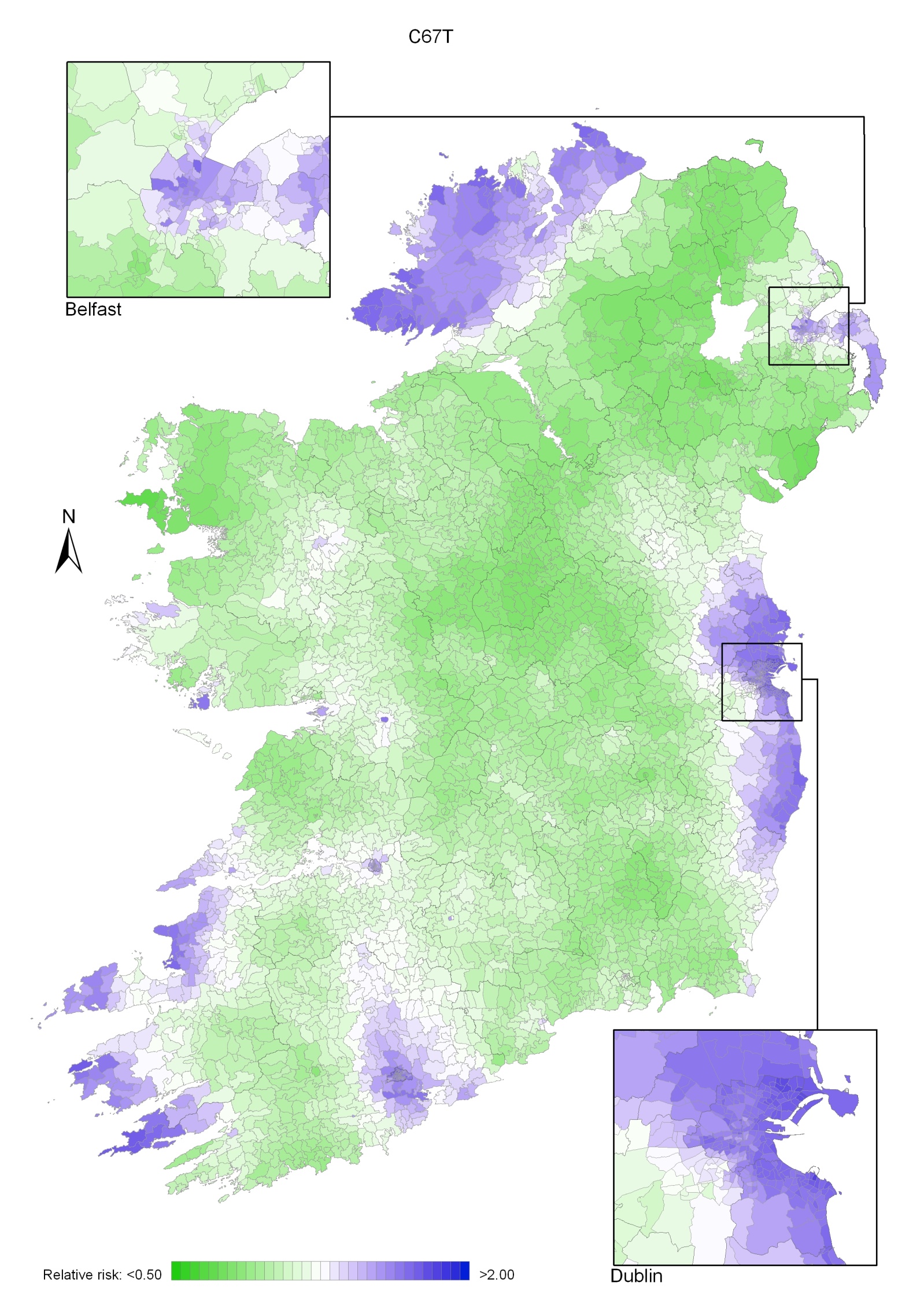

For women the geographical variation was less distinct (Map 11.3). As for men, there was an area of higher relative risk along the east coast, but there was a second area of increased risk which included most of Munster—a much larger area than for men. Donegal and parts of Belfast showed slightly increased levels of relative risk.

Map 11.1 Bladder cancer, smoothed relative risks: both sexes

Map 11.2 Bladder cancer, smoothed relative risks: males

Map 11.3 Bladder cancer, smoothed relative risks: females