14. Pancreatic cancer

14.1 Summary

Pancreatic cancer was the eleventh most common cancer in Ireland, accounting for 2.6% of all malignant neoplasms, excluding non-melanoma skin cancer, in women and 2.5% in men (Table 14.1). The average number of new cases diagnosed each year was 272 in women and 269 in men. During 1995-2007, the number of new cases diagnosed showed an overall increase of approximately 4% per annum.

The risk of developing pancreatic cancer up to the age of 74 was 1 in 169 for women and 1 in 123 for men and was similar in RoI and NI. At the end of 2008, 101 women and 115 men aged under 65, and 197 women and 154 men aged 65 and over, were alive up to 15 years after their pancreatic cancer diagnosis.

Table 14.1 Summary information for pancreatic cancer in Ireland, 1995-2007

Ireland | RoI | NI | ||||

females | males | females | males | females | males | |

% of all new cancer cases | 1.9% | 1.8% | 2.0% | 1.8% | 1.7% | 1.8% |

% of all new cancer cases excluding non-melanoma skin cancer | 2.6% | 2.5% | 2.8% | 2.5% | 2.3% | 2.4% |

average number of new cases per year | 272 | 269 | 192 | 189 | 80 | 81 |

cumulative risk to age 74 | 0.6% | 0.8% | 0.6% | 0.8% | 0.5% | 0.8% |

15-year prevalence (1994-2008) | 298 | 269 | 239 | 198 | 59 | 71 |

Pancreatic cancer is a disease of older people; fewer than 20% of new cases were diagnosed in persons under 60 years old, while almost 60% presented at 70 years or over (Figure 14.1). The average age at diagnosis was older for women than men, with a similar age distribution in RoI and NI.

Figure 14.1 Age distribution of pancreatic cancer cases in Ireland, 1995-2007, by sex

14.2 International variations in incidence

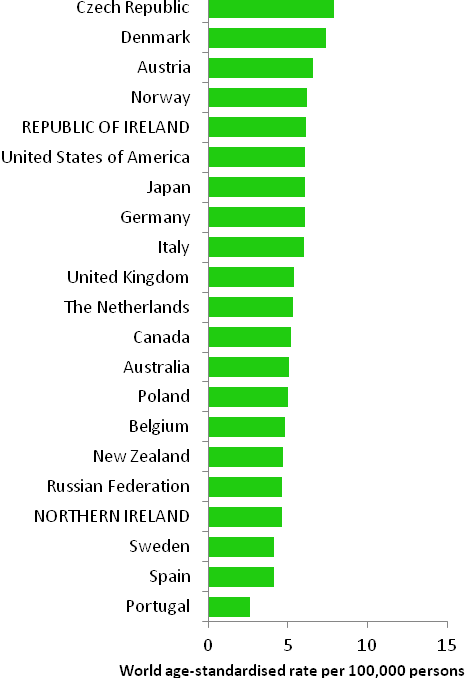

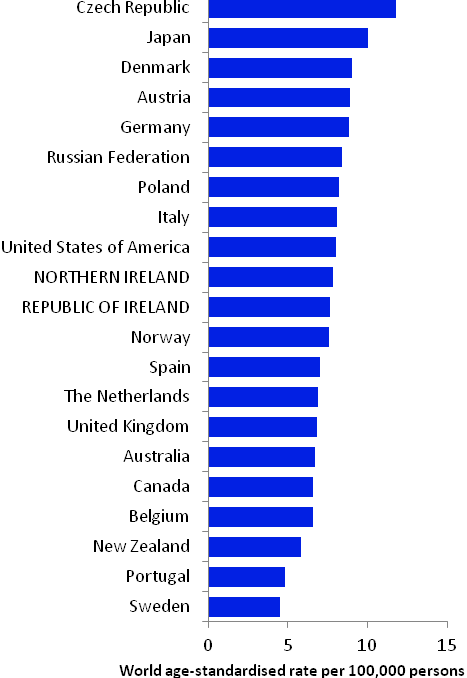

Pancreatic cancer rates were highest in the Czech Republic for both men and women, and lowest in Sweden for men and in Portugal for women (Figure 14.2). Male rates of pancreatic cancer in both RoI and NI were close to the median of the countries shown; for women, they were below the median in NI and above the median in RoI.

Figure 14.2 Estimated incidence rate per 100,000 in 2008 for selected developed countries compared to 2005-2007 incidence rate for RoI and NI: pancreatic cancer | |

| females | males |

|  |

Source: GLOBOCAN 2008 (Ferlay et al., 2008) (excluding RoI and NI data, which is derived from Cancer Registry data for 2005-2007) | |

14.3 Risk factors

Table 14.2 Risk factors for pancreatic cancer, by direction of association and strength of evidence

| Increases risk | Decreases risk |

Convincing or probable | Tobacco smoking1 | |

| Smokeless tobacco1,2 | |

| Alcohol1,3,4 | |

| Chronic pancreatitis5 | |

| Diabetes6,7 | |

| Greater body fatness/abdominal fatness8,9 | |

| Height/tallness10 | |

| Occupational exposure to styrene11 | |

| Family history of pancreatic cancer12,13,14 | |

Possible | Involuntary (passive) smoking15,16 | Metformin19 |

Insulin resistance/metabolic syndrome17 | Physical activity20 | |

Red meat10,18 | Folate10,21 | |

Allergic conditions and/or atopy22,23 | ||

1 Secretan et al., 2009; 2 chewing tobacco or snuff; 3 Michaud et al., 2010; 4 Lucenteforte et al., 2011; 5 Raimondi et al., 2010; 6 Ben et al., 2011; 7 Li et al., 2011b; 8 Jiao et al., 2010; 9 Arslan et al., 2010; 10 World Cancer Research Fund / American Institute for Cancer Research, 2007; 11 National Toxicology Program, 2008; 12 one or more first degree relatives(s) with cancer of the pancreas; 13 Maisonneuve and Lowenfels, 2010; 14 Jacobs et al., 2010; 15 exposure in childhood and/or in adulthood at home or work; 16 Vrieling et al., 2010; 17 Rosato et al., 2011; 18 beef, pork and lamb; 19 Decensi et al., 2010; 20 O’Rorke et al., 2010; 21 found in green leafy vegetables and beans, peas and lentils; 22 including eczema, hay fever and rhinitis; 23 Gandini et al., 2005c | ||

Tobacco smoking is causally related to pancreatic cancer (Table 14.2) and accounts for 20-25% of cases (Maisonneuve & Lowenfels, 2010). Smokers of cigarettes, cigars and pipes are all at increased risk; risk increases with duration of smoking and cumulative smoking dose, and decreases to background levels 15 years after smoking cessation (Lynch et al., 2009). Use of smokeless tobacco is also a causal factor and there are suggestions that individuals exposed to environmental tobacco smoke either in childhood, or at home or work as adults, have increased risk of pancreatic cancer. Alcohol is also causally related to pancreatic cancer although the association appears to be restricted to individuals with high alcohol intake, and may be limited to men.

As regards medical conditions, around 5% of patients with long-term inflammation of the pancreas (chronic pancreatitis) are likely to develop pancreatic cancer over a 20 year period. Diabetics have increased risk, especially insulin users, but some uncertainties remain regarding the association (Magruder et al., 2011). In a few studies, insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome have also been linked to elevated pancreatic cancer risk, while use of metformin as a treatment for diabetes has been associated with reduced risk. Inverse associations have been reported between allergic conditions and atopy and pancreatic cancer risk.

Taller adults have increased risk, but height per se is unlikely to affect risk; it is most probably a marker for a risk factor related to linear growth in childhood. Risk of pancreatic cancer increases with increasing body fatness, by 6% for men and 12% for women per 5kg/m2 increase in body mass index. In addition, most studies which have examined measures of abdominal fatness have reported positive findings. Some other lifestyle-related factors have been linked to pancreatic cancer (e.g. physical activity, aspects of diet), but the evidence regarding these remains somewhat uncertain.

An estimated 5-10% of pancreatic cancers arise as a result of genetic syndromes. One affected first degree relative confers a 75% increased risk.

14.4 Small geographic area characteristics and cancer risk

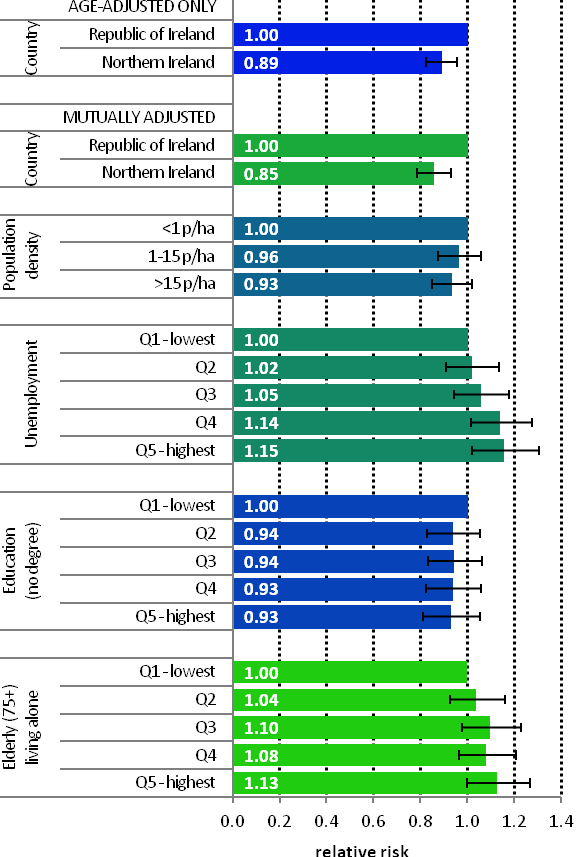

Figure 14.3 Adjusted relative risks (with 95% confidence intervals) of pancreatic cancer by socio-economic characteristics of geographic area of residence: males | MalesAmong men, after adjustment for age, population density and socio-economic factors, pancreatic cancer risk was lower in NI than in RoI (RR=0.85, 95%CI=0.79-0.93). Socio-economic factors accounted for only a small proportion of this difference (Figure 14.3). Male pancreatic cancer was not associated with population density, education or the proportion of persons aged 75 and over living alone. Unemployment was positively associated with male pancreatic cancer, with a steady increase in risk as unemployment levels in an area increased. |

Figure 14.4 Adjusted relative risks (with 95% confidence intervals) of pancreatic cancer by socio-economic characteristics of geographic area of residence: females

| FemalesThe risk of pancreatic cancer in women was 22% lower in NI than in RoI; as in men adjustment for socio-economic factors had a relatively small effect on this difference (Figure 14.4). As with men, there was no significant variation in risk of female pancreatic cancer by population density. However, unlike men, there was no association with unemployment and a positive association with lower educational attainment. Areas with the highest proportion of persons aged 75 and over living alone had a 16% greater risk of female pancreatic cancer than areas with the lowest proportion. |

14.5 Mapping and geographical variation

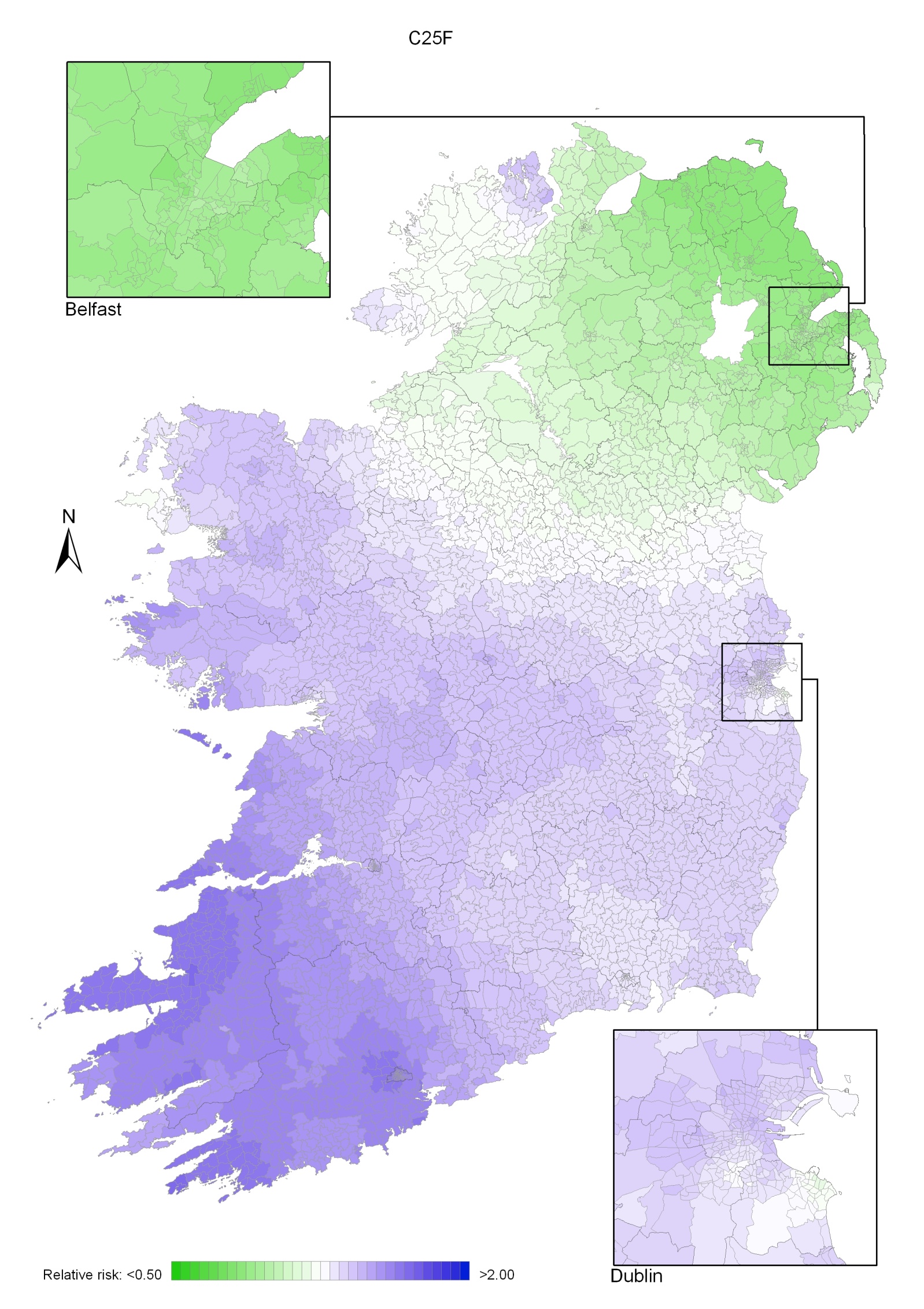

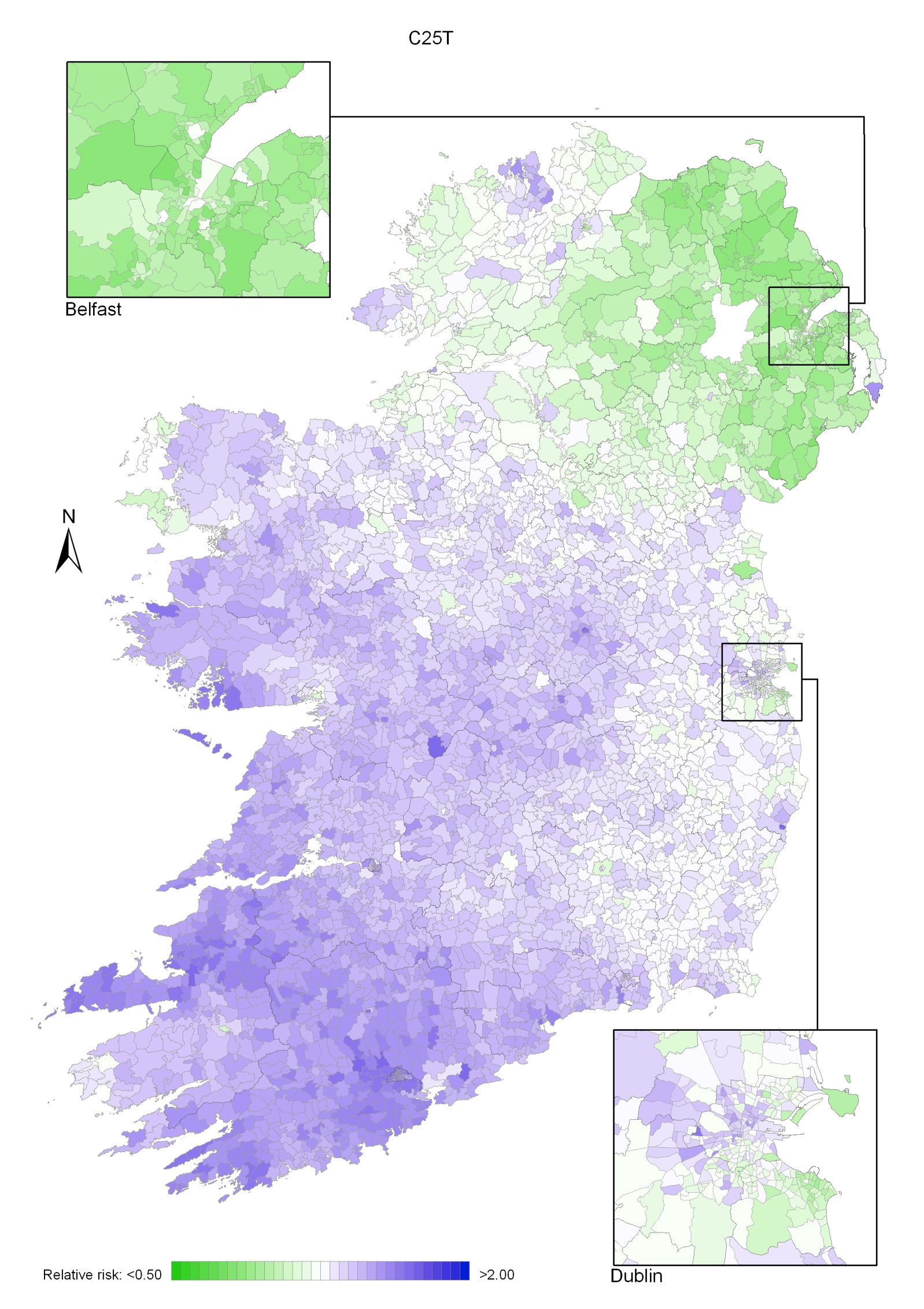

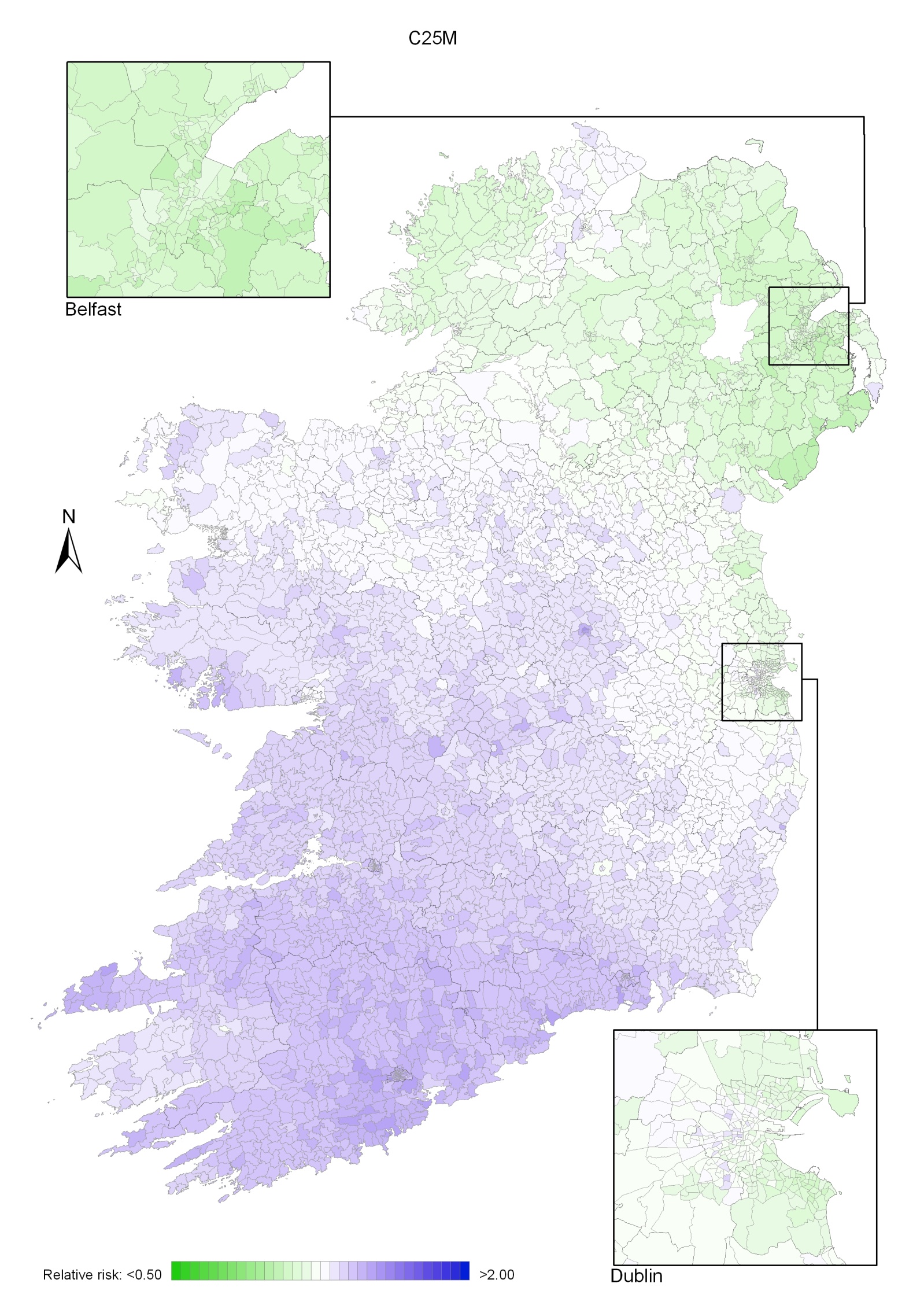

Pancreatic cancer had a strong geographical pattern which was similar for men and women (Maps 14.1-14.3).

This consisted of a fairly smooth gradient, from the area of lowest risk in the north-east to the area of highest risk in the south-west (Map 14.1), highest around Cork city for men (Map 14.2) and centred on north Kerry in women, for whom there were also some areas of higher risk in Donegal (Map 14.3). The variation in risk was more pronounced for women than for men.

Map 14.1 Pancreatic cancer, smoothed relative risks: both sexes

Map 14.2 Pancreatic cancer, smoothed relative risks: males

Map 14.3 Pancreatic cancer, smoothed relative risks: females