Oesophageal cancer was the thirteenth most common cancer in Ireland, accounting for 1.8% of all malignant neoplasms, excluding non-melanoma skin cancer, in women and 2.7% in men (Table 16.1). The average number of new cases diagnosed each year was 182 in women and 301 in men. During 1995-2007, the number of new cases diagnosed increased by approximately 2% per annum.

The risk of developing oesophageal cancer up to the age of 74 was 1 in 258 for women and 1 in 105 for men and was similar in NI and RoI. At the end of 2008, 118 women and 278 men aged under 65, and 308 women and 423 men aged 65 and over, were alive up to 15 years after their oesophageal cancer diagnosis.

Table 16.1 Summary information for oesophageal cancer in Ireland, 1995-2007

Ireland | RoI | NI | ||||

female | male | female | male | female | male | |

% of all new cancer cases | 1.3% | 2.0% | 1.3% | 1.9% | 1.3% | 2.2% |

% of all new cancer cases excluding non-melanoma skin cancer | 1.8% | 2.7% | 1.8% | 2.7% | 1.7% | 2.9% |

average number of new cases per year | 182 | 301 | 122 | 202 | 60 | 98 |

cumulative risk to age 74 | 0.4% | 1.0% | 0.4% | 0.9% | 0.4% | 1.0% |

15-year prevalence (1994-2008) | 426 | 701 | 289 | 454 | 137 | 247 |

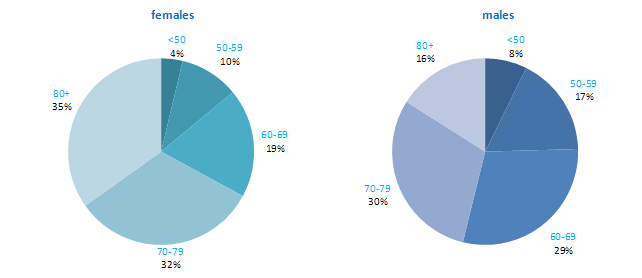

The age distribution at diagnosis was different for men and women (Figure 16.1). More than half of men, but only one-third of women, presented at under 70 years of age, while a further third of women, but only 16% of men, was aged 80 years or older at diagnosis. The pattern was similar in RoI and NI.

Figure 16.1 Age distribution of oesophageal cancer cases in Ireland, 1995-2007, by sex

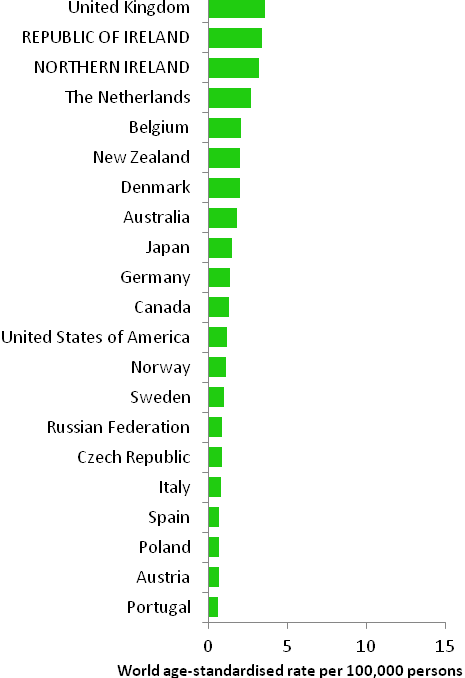

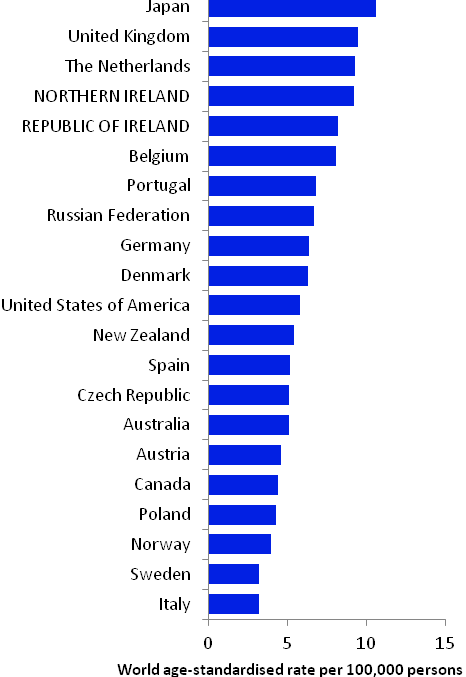

Among developed countries, only the UK had higher rates of oesophageal cancer in women than NI and RoI (Figure 16.2). Among men, NI and RoI also had relatively high rates of the disease, with only UK, Netherlands and Japan having higher rates. The lowest rates were in Sweden and Italy for men and in Austria and Portugal for women.

Figure 16.2 Estimated incidence rate per 100,000 in 2008 for selected developed countries compared to 2005-2007 incidence rate for RoI and NI: oesophageal cancer | |

| females | males |

|  |

Source: GLOBOCAN 2008 (Ferlay et al., 2008) (excluding RoI and NI data, which is derived from Cancer Registry data for 2005-2007) | |

Table 16.2 Risk factors for oesophageal cancer, by direction of association and strength of evidence

| Increases risk | Decreases risk |

Convincing or probable | Tobacco smoking1,2,3 | Non-starchy vegetables6,14 |

| Smokeless tobacco3,4 | Fruit6,14 |

| Alcohol3,5 | Foods containing beta-carotene6,15 |

| Greater body fatness/higher body mass index6 | Foods containing vitamin C6,16 |

| Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease7 | Helicobacter pylori infection17,18 |

| Low socio-economic status8 | Aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs19,20 |

Possible | Red meat6 | Gastric atrophy (adenocarcinoma)13 |

| Processed meat6 | |

| Pickled vegetables9 | |

| High temperature drinks10 | |

Infection with human papilloma viruses (HPV)11 | ||

Occupational exposure to hexavalent chromium12 | ||

Gastric atrophy (squamous cell carcinoma)13 | ||

1 International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2004b; 2 Boffetta et al., 2008; 3 Secretan et al., 2009; 4 chewing tobacco or snuff; 5 Islami et al., 2010; 6 World Cancer Research Fund / American Institute for Cancer Research, 2007; 7 Pera et al., 2005; 8 Faggiano et al., 1997; 9 Islami et al. 2009a; 10 Islami et al., 2009b; 11 International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2007; 12 Gatto et al., 2010; 13 Islami et al., 2011; 14 International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2003; 15 beta-carotene is found in yellow, orange and green fruits and green leafy vegetables; 16 vitamin C is found in fruit, vegetables and tubers;17 Islami and Kamangar, 2008; 18 Rokkas et al., 2007; 19 Bosetti et al., 2006; 20 Abnet et al., 2009 | ||

The two main types of oesophageal cancer are squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. Some risk factors are shared by both types, while others are involved in one type only. Tobacco smoking causes both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus (Table 16.2). Smokers have at least a two-fold higher risk than non-smokers and risk increases with number of cigarettes smoked daily and duration of smoking. Use of smokeless tobacco products (e.g. snuff, chewing tobacco) is also associated with increased disease risk. Alcohol is also causally related to oesophageal cancer and risk increases with amount consumed.

Obesity and overweight are positively associated with adenocarcinoma. In contrast, higher levels of body fatness are either unrelated to risk of squamous cell carcinoma, or associated with a decreased risk (Smith et al., 2008). A history of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease has been associated with increased risk of adenocarcinoma, but not of squamous cell carcinoma. Gastric atrophy may be positively associated with squamous cell carcinomas and negatively associated with adenocarcinoma. Infection with the Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) bacterium has been associated with reduced risk of adenocarcinoma, while infection with human papilloma virus may play a role in squamous cell carcinoma.

Various aspects of diet have been linked with oesophageal cancer risk. Higher intakes of fruit and vegetables, particularly those containing beta-carotene (yellow, orange and green fruits and green leafy vegetables) or vitamin C, probably reduce risk. Higher intakes of red or processed meat may increase risk, but the evidence is less consistent than for fruit and vegetables. Risk may also be increased in those with higher intakes of pickled vegetables, and those who prefer to consume their hot drinks at a high temperature.

Risk of oesophageal cancer is higher in those of low socio-economic status, probably reflecting variations in exposure to tobacco and other lifestyle risk factors by social class.

Figure 16.3 Adjusted relative risks (with 95% confidence intervals) of oesophageal cancer by socio-economic characteristics of geographic area of residence: males | MalesThere was little difference between NI and RoI with regard to risk of male oesophageal cancer, either with or without adjustments for socio-economic factors and population density (Figure 16.3). Risk of oesophageal cancer increased with increasing population density, with the most densely populated areas having a 21% increased risk compared to the least densely populated areas. Neither education nor unemployment was associated with male oesophageal cancer overall. However, men resident in quintile 4 of the unemployment measure had a slightly (15%) elevated risk of the disease. Oesophageal cancer risk was highest (21% above the risk for Q1) in areas with a high proportion of elderly people living alone. |

Figure 16.4 Adjusted relative risks (with 95% confidence intervals) of oesophageal cancer by socio-economic characteristics of geographic area of residence: females

| FemalesThe risk of oesophageal cancer in women was lower in NI than in RoI (RR=0.92, 95%CI=0.84-1.00) (Figure 16.4). Adjusting for differences in socio-economic and population density characteristics in the two countries increased this difference (RR=0.86, 95%CI=0.78-0.95). As with men, the risk of oesophageal cancer among women increased with increasing population density, with the highest density areas having a 21% increased risk compared to the lowest density areas. There was no association between either education or unemployment overall and female oesophageal cancer. However, as for men, an increased risk was identified in areas with a high proportion of elderly people living alone. |

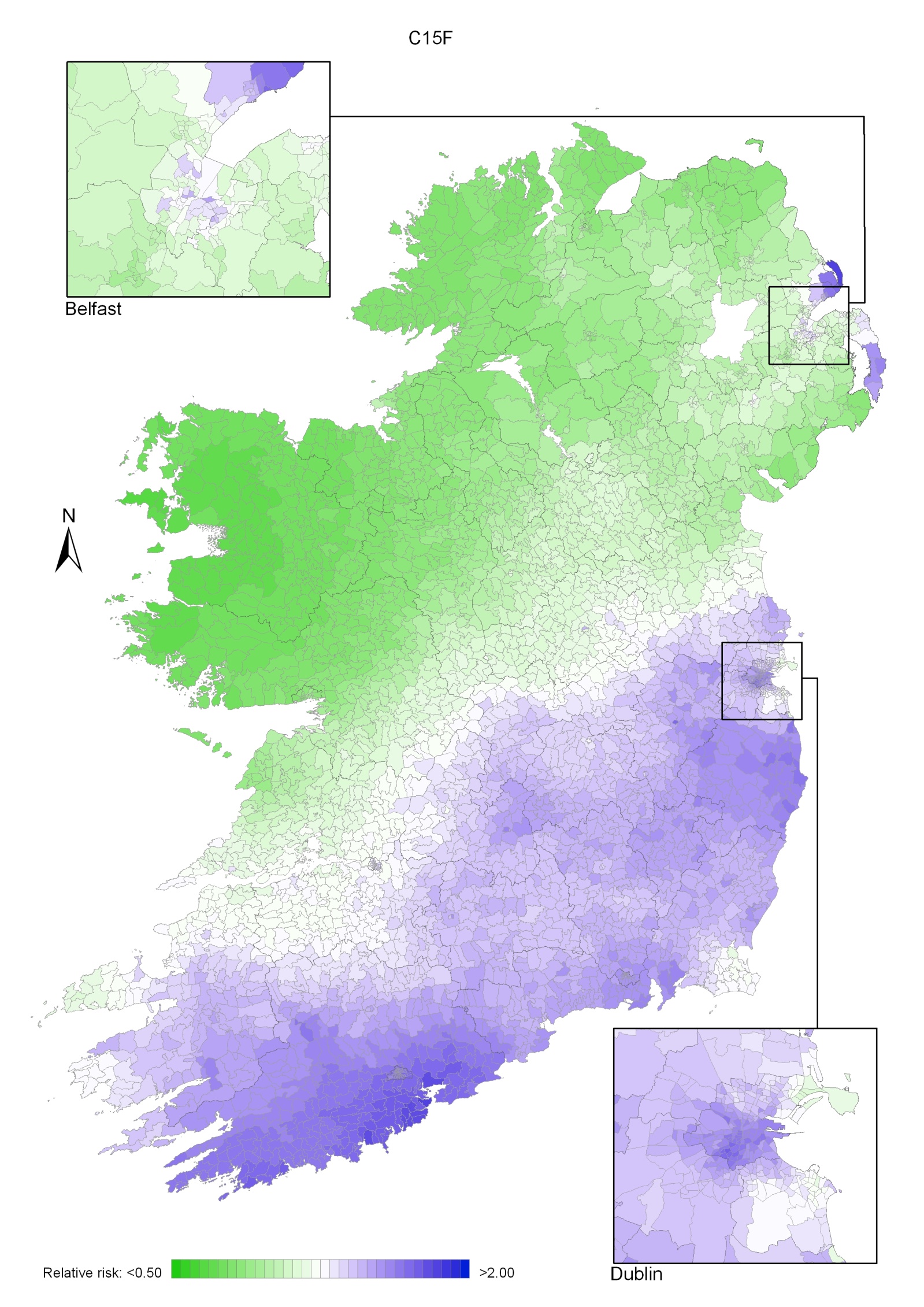

Oesophageal cancer had a strong geographical pattern, which was similar for men and women. For both sexes combined there was a large area of higher relative risk extending south of a line from west Cork to Dublin with smaller areas of higher risk in Belfast, Carrickfergus, Larne and Ards. Areas in the west and north-west had a lower relative risk (Map 16.1).

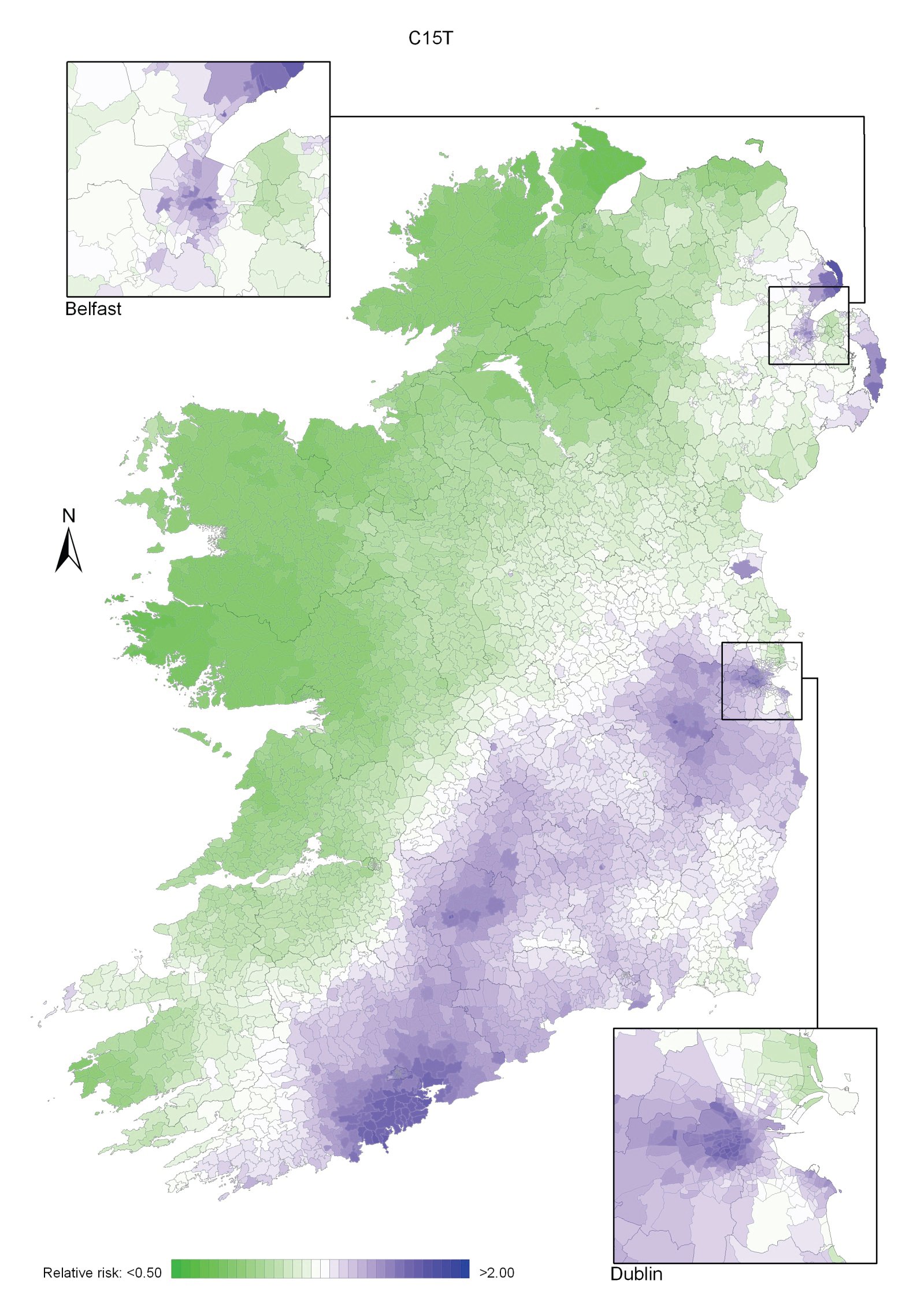

The area of higher relative risk for men was slightly smaller and more diffuse, extending north-eastwards from Cork to the north-east of NI Antrim (including Belfast) and including most of the east of RoI with the exception of the area around Wexford (Map 16.2).

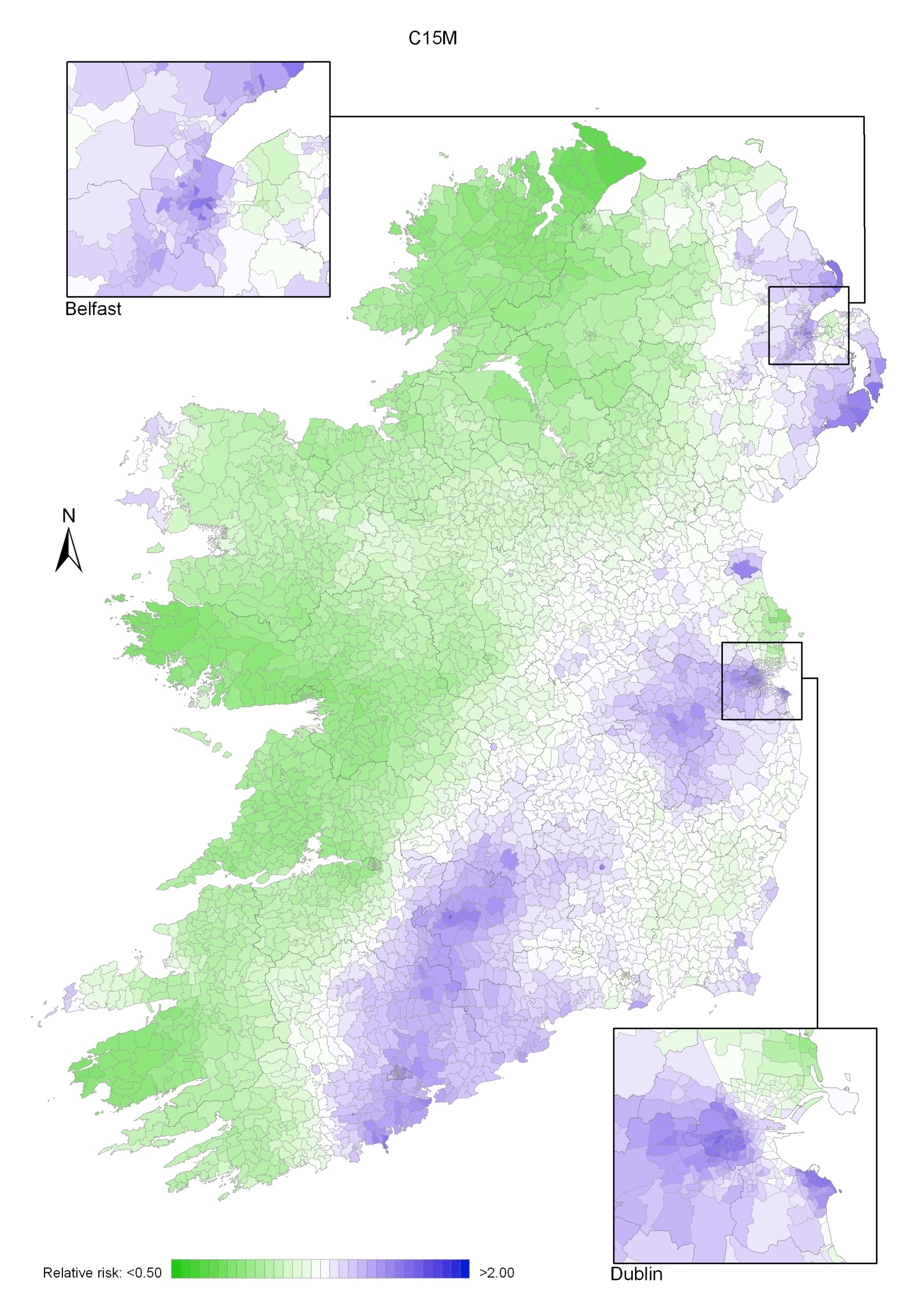

For women, the area of higher risk was more pronounced and there were also small areas of higher risk in Larne, Carrickfergus, Ards, along the Ards Peninsula (Map 16.3).

Map 16.1 Oesophageal cancer, smoothed relative risks: both sexes

Map 16.2 Oesophageal cancer, smoothed relative risks: males

Map 16.3 Oesophageal cancer, smoothed relative risks: females